Overview of PE involvement in the top 5 leagues

The Premier League (England)is the most competitive domestic championship worldwide, where reaching a place granting international competition is an arduous task for one of the non-big six clubs. The average EV of the English clubs among the 32 most valuable European clubs is well above that of the other leagues (based on KPMG Football Benchmark) with an average of €1.71b for Premier League clubs (9 clubs) compared to €1.51b, for Bundesliga (3 clubs), €1.31b LaLiga (6 clubs), €0.70b Serie A (6 clubs) and €0.68b for Ligue 1 (3 clubs). The pioneer for takeovers on English teams was Roman Abramovich, paying only £140m for Chelsea in 2003. Further, Manchester United was acquired in 2005 by Malcolm Glazer through a leveraged buyout, taking the company private after 14 years on the LSE, with the transaction totalling £800m. In 2008, city rival Manchester City was purchased by Abu Dhabi United Group for £210m, receiving a considerable financial investment in staff and players, including the £150m Etihad campus. Liverpool FC was sold to Fenway Sports Group (American parent company of Boston Red Sox) in 2010 for £300m. Smaller clubs have been raising interest, too, with a pair of Appolo and Blackstone executives teaming up to take a controlling share of mid-table side Crystal Palace in 2015. The aforementioned Manchester City also played a crucial role in Silver Lake’s decision to acquire a $500m stake in City Football Group, a holding company that owns a portfolio of different football clubs, in 2019.

The Bundesliga (Germany) is not a viable option for investors seeking control. This is due to the implementation of the so-called 50 +1 rule. This rule was designed to ensure that the club’s members retain overall control by owning 50% of shares +1, protecting clubs from the influence of external investors.

LaLiga (Spain) is very active in changing ownerships for clubs despite their high prices. More recently, it has been very contested, with even some second division clubs receiving investments. The biggest deal in recent years was the Chinese Rastar Group buying Espanyol Barcelona for €150m in 2015. Other notable transactions include the Chinese Wanda Group buying 20% of Atletico Madrid for €45m and Singapore magnate Peter Lim purchasing 70% of Valencia for €94m. Further, Granada was bought in 2016 by the Chinese Link International Sports Limited for €37m, and Ronaldo (Brazilian) acquired a majority stake in Real Valladolid.

Ligue 1 (France) is attractive for foreign investors as the league is not very competitive. Ligue 1 also has the least expensive clubs among the top five leagues (even PSG only cost Qatar Sports Investments €100m in 2011). Furthermore, the biggest deal by implied valuation was the purchase of 20% of Lyon by Chinese IDG Capital Partners for €100m in 2016. Among more recent deals, there was Nice by British energy group INEOS in 2019 and Bordeaux by General American Capital Partners in 2018, both for around €100m.

Serie A (Italy) is probably the most prominent league for foreign investors. First, on the advertising side, it offers one the richest and most prestigious football histories and cultures with several trophies at national and club level and legendary players, which are key assets for branding. Secondly, clubs are not very expensive in relative comparison. Among the 32 leading clubs in Europe, the six Italian ones are, worth approximately half of the Spanish ones and only a third of the English clubs. Despite the great potential of this league, only six clubs have foreign ownership, and most of them are owned by families. Roma was the first club that switched to foreign control when in 2011, Thomas Di Benedetto (Italian-American) bought a 67% controlling share for €70m from the local Sensi family. In 2020, the Sensi family sold the club to the American Friedkin Group, which paid €780m to buy the club. Subsequently, Bologna FC was sold for only €7m in 2014 to Italian-American investors. More recently, in 2019, local family Della Valle sold Fiorentina for €165m to Rocco Commisso, another Italian-American investor. The most significant part of public attention remains reserved for the two Milanese clubs, who had some turbulent years in changing ownerships. The Suning Group bought a 68.55% stake of Inter for €270m in 2016. On the other side of the street, AC Milan was sold in 2016 from Silvio Berlusconi to Li Yonghong for €828m. After two years of mismanagement, Elliot Capital took full control by executing a guarantee on a €415m default by the previous owner.

Recent Trends & Outlook

As covered throughout the paper, the football industry is going through a profound transformation as the financials of leagues, clubs, and competitions are getting more attractive for investors. Additionally, today football clubs and leagues are under pressure to look after financing to help steer their balance sheets through the Covid-19 pandemic. As a response to this, we have seen unprecedented interactions between the financial and the football industries. We assess three of the most distinguished ones below:

- Buying the League & Fire Sale Prices

The revenue plunge in football caused by the Covid19 pandemic has led many of Europe’s most famous football leagues to proactively look for additional income streams, with the top-flight divisions of Germany, Italy and Spain all proposing to create separate vehicles owning media and/or commercial rights. While the sports governing bodies would hold the majority of shares in these vehicles, minority stakes could be sold to investors to Such talks have been particularly advanced between the Italian Serie A and a PE consortium led by CVC, with an offer of $1.6bn in exchange for a 10% stake in such a commercial vehicle rumoured to be on the table since February. However, talks have been on hold as several big Italian teams feel the amount does not match the actual value of such a stake.

Although the concept of “Buying the League” would be somewhat of a novelty in football, it has been tested in other sports. In racing, Formula1 and MotoGP were owned by CVC (exited in 2017) and Bridgepoint. Furthermore, talks between Silver Lake and the New Zealand Rugby Union are in the final stages. Critics are voicing concerns that allowing Private Equity funds to take partial control of the governing bodies of domestic football competitions would be an irreversible step towards the expropriation of the sport from local communities.

At the individual-club level, investors are eyeing bargain deals due to the current health emergency, too. US Private Equity firm ALK Capital recently acquired Burnley FC through a leveraged buyout. The price of $270m seemed relatively low, considering that the Lancashire-based Premier League outfit has established itself as a solid mid-table team in the most profitable domestic competition over the last couple of years. Due to the nature of the takeover, supporters are concerned that ALK Capital might not actually be looking to build the club up by investing but rather to squeeze out as much as possible from the existing setup before selling again.

It remains to be seen how quickly domestic leagues and individual clubs will manage to recover from the financial damages caused by the Covid19 pandemic. If it turns out that the debts taken on during this period are too heavy to deal with traditionally, talks for external funding could gain further momentum.

2. European Super League

The recently proposed idea of the European Super League (ESL), spearheaded amongst others by clubs owned by Private Equity funds, represents an existential threat to domestic football associations across Europe and a direct attack on UEFA, their superordinate governing body. The idea is to squeeze more money out of the European top football contest. The Champions League, which would have been effectively replaced, currently generates around €3bn of revenue and typically pays out ~ €2bn overall to participant teams who earn at least €25m and up to €120m. In contrast, the ESL was aiming for €4bn a year for its media rights. The rebel collective of breakaway clubs was going to be funded by JP Morgan in the first stages, which had committed more than $4bn as an “infrastructure grant” in debt financing amortised over 23 years and secured against broadcasting rights for the tournament. The amount was meant to initially cover a “welcome bonus” worth €200-300m for each of the 12 participant clubs. In truth, the “welcome bonus” was merely an advance on future revenues that would have to be repaid if any club chose to leave the competition.

The announcement of the ESL comes as clubs across Europe have suffered steep revenue shortfalls due to the pandemic, raising concerns over the sustainability of their business models and complicating any plans for new player signings. The timing also coincides with a period that has seen the valuations for top-tier franchises proliferate, prompting questions over where these clubs would find new sources of revenue.

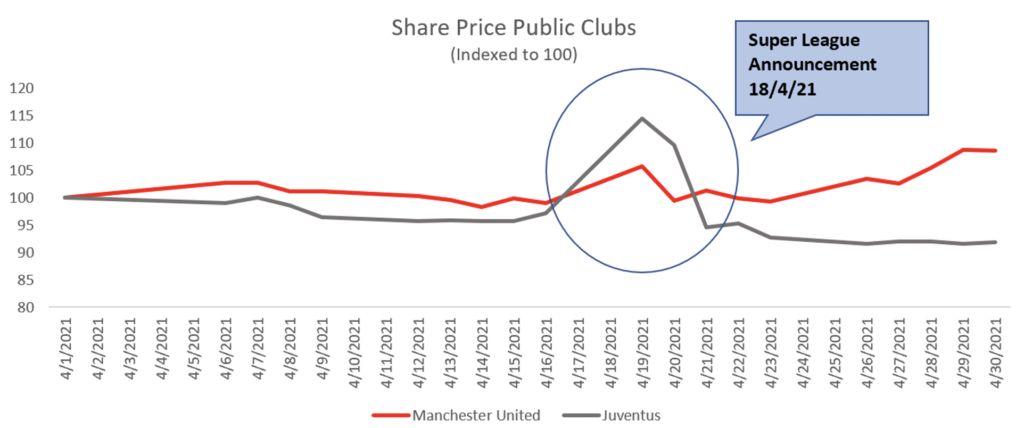

The plan quickly collapsed. Shortly after the announcement, all six UK clubs pulled out. Following them, AC Milan, Inter Milan, Atletico Madrid withdrew as well. Subsequently, JPMorgan stated regretting backing the ESL, arguing that they misjudged the perception of the wider football community. It is well known that ESL aroused great anger, manifestations, and myriad critics by football fans worldwide. However, public markets/ investors liked the idea, as seen in a spike in the share price of listed clubs (figure 3) following the announcement. Juventus’ share price surged nearly 19%, and the one of Manchester United rose 9%.

Comments are closed.