by Edoardo Miccio and Francesco Monteduro

Introduction

This article will provide the reader with a deeper understanding on the reasons why club deals, also known as consortiums or syndicated investments, have increased in popularity in recent times, whilst also assessing the advantages and disadvantages of the practice. Before analyzing historical trends and the recent boom in club deals, as well as the reasons why Private Equity firms simultaneously favor and despise this type of investment, Club Deals are defined and further specified.

In financial jargon, a club deal is defined as a buyout or Private Equity investment undertaken by multiple Private Equity in which the involved firms pool their assets together and proceed jointly with the investment. Such investment strategies allow Private Equity funds to exert control over companies that would not have been suitable for a sole-sponsored acquisition, minimizing risk and exposure and exploiting potential synergies.

The Advantages of Club Deals

Club deals, and their effectiveness, have been the subject of intense debate and indeed criticism ever since the strategy’s inception, yet investor and manager opinions on the practice have changed over the last few decades. As a matter of fact, the last few years have seen the annual number of club deals grow at a surprisingly fast rate, increasing the practice’s public exposure among firms and academics, further fueling the associated debate whilst also shedding some light on related advantages.

But why do Private Equity firms continue to pursue club deals when the practice faces widespread criticism? First, a club deal allows a firm to reduce its risk and potential losses by sharing a project’s risk with the consortium’s partners. It follows that the practice presents an effective way to conclude large leveraged buyouts relying on a substantial amount of debt financing, or ambitious investments that bear a high degree of risk. Another primary advantage of club deals links to the practice of leveraged buyouts (LBOs). Since LBOs require a large volume of debt financing, consortiums can access a larger volume of funds through loans whilst leveraging a higher bargaining power to conclude better deals with lenders, compared to if they attempted an LBO as a single firm. This is because consortiums are seen as more reliable and less likely to default and because they have a larger pool of assets to be used as collateral. Through club deals a PE firm can also pursue a strategy of diversification by investing its limited funds into different projects and across different sectors, protecting the company from external losses. Finally, one can suggest that club deals can exploit the synergies deriving from the sharing of resources by each PE firm. The various steps associated with an acquisition can be streamlined by collaborating with other PE firms, since associated tasks can be allocated based on the specific proficiencies of each firm. Club deals also take advantage of each firm’s extended network and partnerships, facilitating the process if need be.

The Disadvantages of Club Deals

The following section elaborates on the disadvantages that PE firms may face when engaging in a club deal, whilst linking recent trends and the reluctance by some major PE firms to enter consortiums.

The main issues associated with club deals emerge in the so-called “managing and monitoring” phase of a Private Equity investment. While in the fundraising and deal making phases it is easier for firms to align their interests and direct their efforts to a common goal, several strategic issues may arise when it comes to managing the newly acquired company. This phenomenon is more common when a consortium is made of financial institutions with different individual objectives, organizational cultures, or even sectorial origins. Firms that engage in club deals will inevitably lose their autonomy and the possibility to freely manage the target company. Therefore, leading PE funds such as Blackstone tend to avoid club deals unless they intend to acquire extremely large companies, usually through an LBO. One of the most recent examples is the $34bn Medline LBO which will be described later. In addition to the managerial issue, it is also implied that the lower risks associated with a club deal may imply lower returns. As previously discussed, retaining a share of an acquired company limits the losses in case of bankruptcy or a low exit price, but on the other hand it reduces the returns per firm in the case of a successful investment. Therefore, when firms pinpoint an interesting and relatively safe opportunity, they usually prefer to approach the investment alone to maximize their potential returns. A further source of criticism on club deals links to the accusations of collusion made against PE funds in the first decade of the 21st century. Consortiums were blamed for pushing competitors out of the market to drive down the purchasing prices below the actual market value of the targeted companies. In 2006 the Department of Justice started a formal investigation on this matter and in the following two years filed class actions against several PE firms, weakening the bargaining power of consortiums by affecting the view of potential target companies on club deals. To prove this statement, in 2007 General Electric announced to the possible buyers of its plastic unit that they would not sell to firms that presented an offer through a consortium.

The Origin and Rise of Club Deals

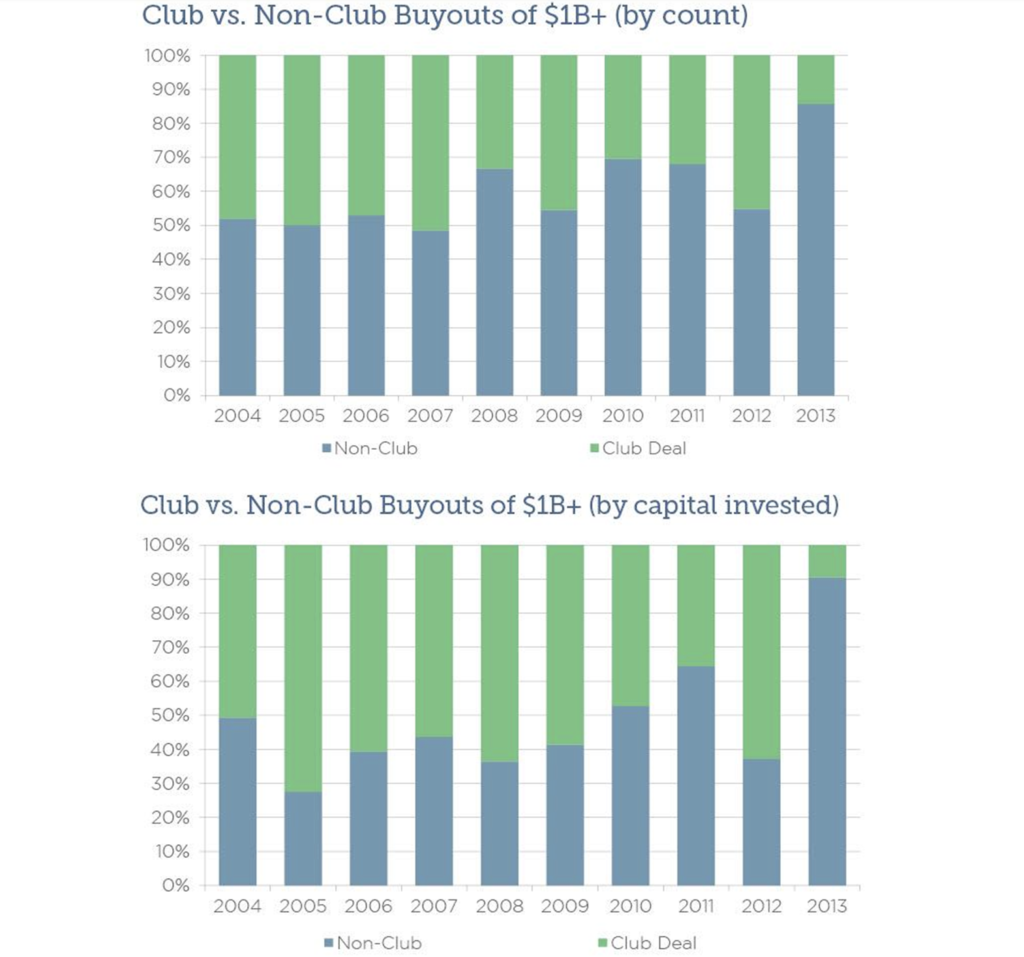

Financial institutions joining forces to conclude transactions that would otherwise be too expensive and difficult to handle was established as a practice centuries ago. Jay Cooke can be considered the pioneer of this revolutionary concept of finance. In 1870, he was the first to promote collaboration in the issuance process by employing an underwriting syndicate, the temporary constitution of a group of investment banks that cooperate to sell or purchase securities, in the sale of a $2m bond issue of the Pennsylvania Railroad. As soon as the financial world caught on that this new procedure enabled firms to assimilate their resources and expertise to simplify difficult operations the practice increased in popularity. The phenomenon then spread across the US very quickly and by the 1920s most of the difficult transactions regarding securities were handled through syndicates. Ever since then the possibility of a consortium of different financial entities has been a key factor to consider in issuances. It is clear how the idea behind syndicate engagements in the issuance of securities can be addressed as the ancestor of the club deal in Private Equity. Given all the advantages of this cooperation, the notoriety of club deals rose year after year reaching its peak between 2003 and 2007, the so-called “era of club deals”. As the graphs below (structured into deal count and invested capital) show, during these years fund consortiums represented half of all the large deals (>$1bn) in Private Equity, expressing the propensity of firms to join forces when entering substantial investments. This is enforced by the fact that the 60% of capital invested in those deals was raised through club deals.

The Decline

Due to the combination of several adverse factors, the 2008 financial crisis marked the end of the so-called “era of club deals” and the beginning of the practice’s end. First, the financial crisis led to a universal decrease in all Private Equity activity, particularly when related to large deals which were increasingly difficult to exit, presenting unreasonable risk. It followed that club deals would lose their prominence as a result. Furthermore, by the time the global economy overcame the crisis and the interest in larger deals rebounded, consortiums did not regain strength since firms were no longer structurally adapted to cooperation and synergetic performance. Hence, it can be inferred that the financial crisis brought down the syndicated investment.

The preceding graph reflects this pattern, representing the steady decrease in club deals after 2008, with buyouts reaching their lowest value in 2013. As a practical representation of this trend one can note the large-scale bankruptcy of the Energy Holdings Group in 2014, bought by KKR and TPG Capital for $48bn in 2007, an example of how a consortium of different PE firms failed due to the associated problems like managerial failure and coordination difficulties. Moreover, the recent years have been characterized by a growing aversion of partners to seek collaboration between funds in favor of the implementation of co-investment programs, where entities co-invest directly in specific funds, resulting in lower management fees. As stated, another reason for the decline links to the legal risks associated with accusations of collusion between firms and the resulting decrease in competition intended to lower the acquisition price. Class action lawsuits fueled the reluctance among shareholders to sell target companies to fund consortiums, as was the case with General Electric. The combination of these factors resulted in a large decrease in the number of club deals in 2018, only accounting for 20% of all buyouts made in the U.S in the same year. However, data seemed to suggest that the situation was destined to change.

The Recent Boom in Activity

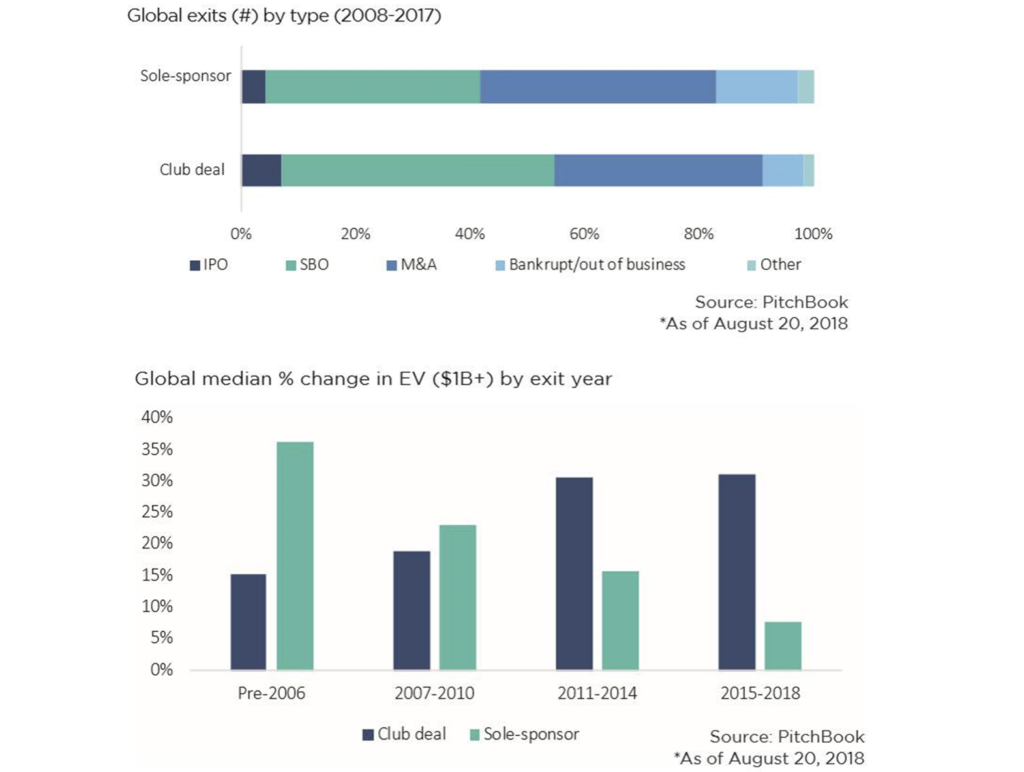

Despite the pandemic, there has been a resurgence in the number of club deals taking place over the last years, suggesting that the practice has reclaimed its strategic prominence. Most PE firms froze their operations in 2020, with most of the funds raised in 2019 going unused. Hence, when economic activity eventually picked up, the result was an excess of dry powder, estimated at around $1.9tn. The resulting abundance in financing packages along with the low interest rates enabled PE firms to close countless deals through consortiums, boosting the M&A market substantially. According to Statista, the buyout deal value doubled from $577bn in 2020 to $1.121tn in 2021, exceeding the previous growth record of $804bn in 2006. Following this pattern, 2022’s first quarter saw buyout groups account for $288bn in deals, a 17% rise from the first quarter of 2021. Furthermore, the volume of dry powder presented an opportunity for funds to expand their investments’ horizons by targeting larger companies. A report from Bain & Company noted that the number of large deals increased by 57%, along with an increase in the average deal size, which eventually reached $1.1bn. Anyhow, the higher dry powder widespread amongst many PE players makes the competition fiercer and the price of deals more sensitive to the presence of several bidders, further raising the willingness of funds to join forces. Nonetheless, several other factors have induced the resurgence in club deals. Among all the advantages, this period of economic uncertainty has made diversified portfolios more attractive. Moreover, Pitchbook data confirmed that club-sponsored buyouts are less inclined to go bankrupt; represented by the graph below. Between 2008 and 2017, 7.2% of club deals declared bankruptcy, whilst 14.5% of sole-sponsored funds declared bankruptcy within the same period. The appeal of club deals is also fueled by their performance; with another Pitchbook article highlighting an interesting pattern in exit enterprise values for club-sponsored large deals. From 2006 to 2018 the average percentage change in expected value for consortiums has doubled, reaching 30%, while for sole-sponsored investments the value has decreased to less than 10%.

Notable Club Deals

To underline the data, practical examples are presented to expand on the resurgence of club deals in the financial landscape. First, we will comment on a recent and resounding club deal marked by a staggering valuation, the buyout of Medline Industries for $34bn. This club deal was conducted by a consortium composed of Blackstone, The Carlyle Group, and Hellman & Friedman in late 2021. According to data from S&P’s LCD, the equity provided by all the PE firms amounted to $14.8bn, making it the largest LBO of the last decade and the fourth largest of all time.

The last months of 2021 saw another important buyout take place, with Hellman & Friedman and Bain Capital acquiring Athenahealth for $17bn, a leading supplier of cloud-based enterprise software for medical groups and health systems. The beginning of 2022 has lived up to the previous year’s volume, seeing as two major buyouts driven by different consortiums of PE firms have already taken place, both promoted by Elliott Management. In January, the American firm completed the largest acquisition of the year, partnering with Visa Equity Partners to buy the software company Citrix for $16.5bn. Additionally, two months later Elliot Management joined forces with Brookfield, a Canadian asset management firm, to buy the television ratings group Nielsen for $16bn. All serving to enforce the described resurgence in club deals

Conclusion

Do club deals represent the future of Private Equity or is their recent popularity destined to decline as it has in the past? It’s impossible to provide a certain answer. However, overall dealmaking will inevitably take a hard hit due to the Russia-Ukraine War, along with the surging inflation and still present effects of the pandemic. The possibility to distribute risk and prevent large losses through club deals still presents a source of encouragement to choose such a practice despite the uncertainty.

Sources

https://www.investopedia.com/terms/c/clubdeal.asp

https://pitchbook.com/news/articles/why-club-deals-might-be-making-a-comeback

https://www.ft.com/content/47c9ec9f-e86e-427e-8a50-34e4a6757852

https://www.ft.com/content/24519628-9c86-4b6e-b38c-e03142afa3ee

https://www.ft.com/content/3993dcba-4cbc-4564-a22e-8c36992589b2

https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052702304163604579531283352498074

Editor: Noah Halbritter

Comments are closed.