Introduction

This article aims to give a perspective on the history of Private Equity and Venture Capital, how they evolved, also looking at the environment as a factor to the industry’s rise.

The Pioneers of the Modern Private Equity Industry

The supposedly first Private Equity firms were established in 1946 in the United States of America.

The American Research and Development Corporation (ARDC) was founded by Georges Doriot, also known as “the father of venture capitalism”, as a Venture Capital and Private Equity firm. Originally it was founded with the aim of providing private funding to businesses run by soldiers who were returning from World War II, boosting private sector investments. J. H. Whitney & Co., founded in 1946, as a Private Equity fund with headquarters in Connecticut, USA, is also thought to have pioneered the development of the Private Equity industry. It was founded with the same aim of financing entrepreneurs with a business plan who were not welcomed by banks after World War II. The founder John Hay Whitney initially put-up $10m for investment. Despite the establishment of Private Equity firms, they remained relatively unimportant for decades.

Venture Capital, Growth Capital, and Leveraged Buyouts

While Private Equity firms itself can be seen as a relatively recent phenomenon, being established in the 1950’s, the utilized methods of Private equity, such as venture capital, growth capital and leveraged buyouts, are said to be “as old as capitalism”.

The supposedly first leveraged buyout was carried out by J.P. Morgan & Co., in 1901, when it bought out the Carnegie Steel Corporation for $480m. Carnegie, who was the previous owner, and his partners, were paid in bonds of the new corporation with a floating interest rate, meaning that the interest rate of the bonds was essentially determined by J.P Morgan. At that time, the acquisition of the Carnegie Steel Corporation by J.P Morgan was more than the entire United States Federal Budget.

However, in 1933, the Glass-Steagall Act passed, limiting the funds that banks had available and making such acquisitions nearly impossible to carry out. This led to the opening of a market segment, later filled by the establishment of Private Equity firms in 1946. The first successful venture capital transaction was carried out by ARDC in 1957, when it invested $70.000 into a startup named Digital Equipment Corporation, which was later valued at over $355m following its IPO.

Venture Capital and Silicon Valley

Venture capital firms originally followed a more “passive Venture Capital model”. How can we distinguish between a passive VC model and an active one?

In a passive model, Venture Capital firms make a larger number of smaller investments, and do not become actively involved in guiding the companies. The VC firm then has the opportunity to make follow-on investments in the companies that prove to be promising: this method allows for greater portfolio diversification and risk spreading.

In an active model, Venture Capital firms make a small number of larger investments and are actively involved in guiding companies to reach success. The VC firm usually gets a deeper understanding of the business and can add value to the company but at the cost of less diversification and higher risk.

The passive VC model is still largely present nowadays, even though there are forces towards creating more activist VC companies, and statistics that back the greater success of the latter.

Economically, prior to the birth of Venture Capital firms, there was a structural shift from large to small firms: Fortune 500 companies lost 4 million jobs while simultaneously, companies with under 100 employees added 16 million jobs.

Even though Venture Capital originated in New York, it quickly settled in Silicon Valley, where most of the share of the VC industry settled. This trend was largely due to the Dean of Stanford’s engineering department, who created a tradition for the Stanford faculty members of starting their own companies. The gush of startups and innovation needed financing, which was provided by VC funds that settled in the area. Among the first were Kleiner, Perkins Caulfield & Byers, and Sequoia Capital.

Today, the share of Venture Capital firms settled around the Bay Area and Silicon Valley has dropped down to around 22.7%, and is projected to further drop down, as investors relocate or work from home and secondary tech hubs around the US and the rest of the world gain more importance. Notable events in the Venture Capital industry include the following:

- 1958: With the Small Business Investment Act, the US government grants authority to create new small business investment companies to finance early-stage companies, with a method similar to Venture Capital practices. The effort, however, has been scaled back since the 2000’s.

- 1978: The Revenue Act, a legislation cutting capital gains tax from 49.5% to 28% to encourage the formation of new companies, passed.

- 1970: A relaxation of the limits to pension funds’ commitment to Venture Capital funds was allowed, enabling pension funds to allocate up to 10% of their capital to VC funds. This provided new sources of financing to VC funds, encouraging their growth.

- 1990: At this time, more than 700 VC firms with $143bn AUM were active in the USA, fueled by the dot.com bubble and the establishment of firms such as Google, Yahoo, Netflix and Amazon.

- 1993: The creation of SPACs (Special Purpose Acquisition Companies) by David Nussbaum, initially as blank-check companies used as a last resort exit strategy. Since then, over 500 SPACS have been listed. They were poorly regulated at the start and plagued by penny-stock fraud, but nowadays, SPACs are seen as a safe exit route for VC backed firms. This is especially true during turbulent market periods, such as the COVID-19 crisis, which has contributed to the SPAC boom that had begun in late 2019.

- 2000: The burst of the dotcom bubble, including far more than 1,000 active VC funds, worth around $225bn AUM.

- 2007–2009: The financial crisis. VC’s changed investment strategies, focusing less on later-stage companies and rather on early, startups to postpone IPOs as an exit to avoid lower valuations due to the crisis.

- 2014: The number of VC funds went down to 1206, their worth to $158bn AUM. VC investments, however, were flowing into much later stage investments than in 2000. Furthermore, 25% of investments were made in dollars, compared to 17% in 2000, marking the importance of the US-American market.

- 2014-2021: Expansionary monetary policy contributed to a high availability of credit, promoting leveraged buyouts.

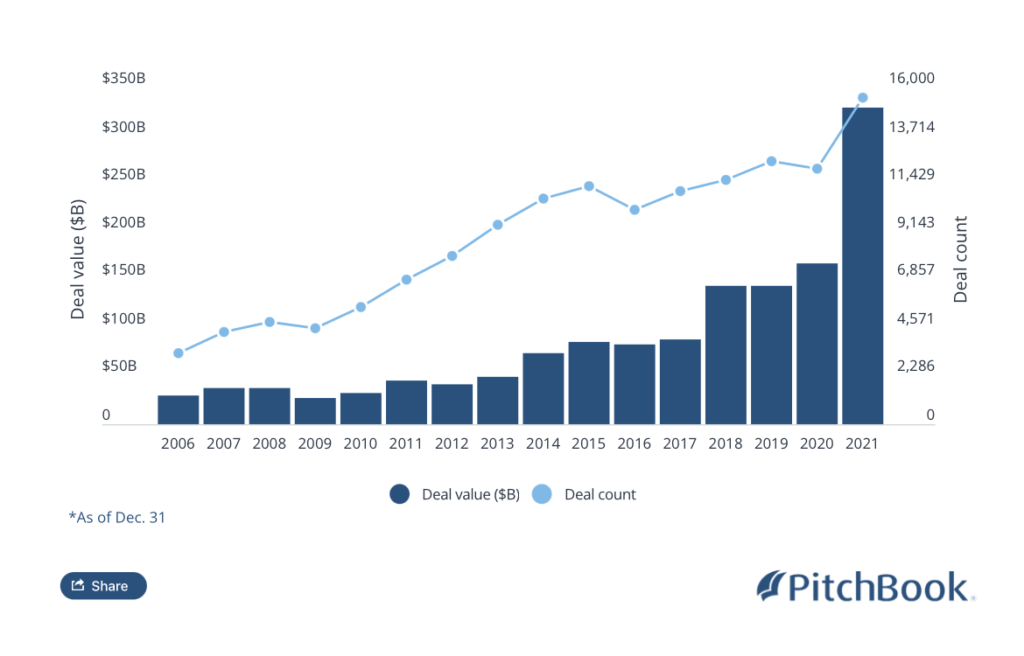

- 2021: The previous year marked a record year for VC investments, and VC-backed companies raised $329.9bn, as is depicted in the figure below.

Venture capital investments over the years:

According to an analysis by PitchBook, VC has been the highest performing private capital asset class in recent years, and nontraditional investors, attracted by high returns, have increased their participation in VC transactions. The record figures experienced globally in 2021 were fuelled by the favourable environment created by strong public markets, valuations and the availability of SPACs and IPOs.

Evolution of the PE Secondary Market

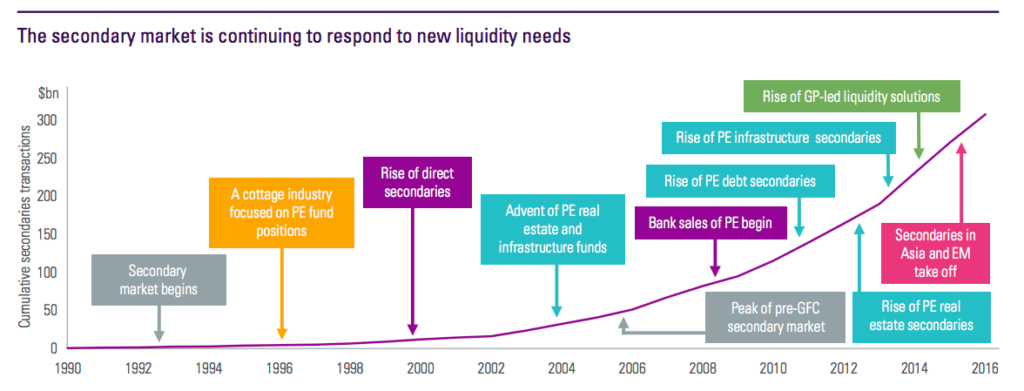

The Private Equity industry as an asset class has always been and still is illiquid and rather long-term, with an average fund lifespan of 15 years. At the beginning of the establishment of PE firms, the PE primary market was prevalent, while over the past decade the secondary PE market has experienced growth, fueled by the financial crisis in 2008. Primary and secondary PE market differ in various aspects: Investments in the primary PE market are directly made in newly formed PE funds, starting from day one; in the secondary PE market, limited partner commitments and pre- existing portfolio companies can be sold and bought by investors.

Secondary PE investments are considered to be more mature than primary PE investments and may have shorter investment periods.

During the financial crisis, in 2008, the growth of the secondary market originated from a distrust in banks and large financial institutions, which led to a strategic sell-off of illiquid PE assets and PE fund commitments on the secondary market. This point in time is represented on the graph below around 2008 as ‘Bank sales of PE begin’, with upward trend on the line representing the secondary market; this trend has made the industry more liquid.

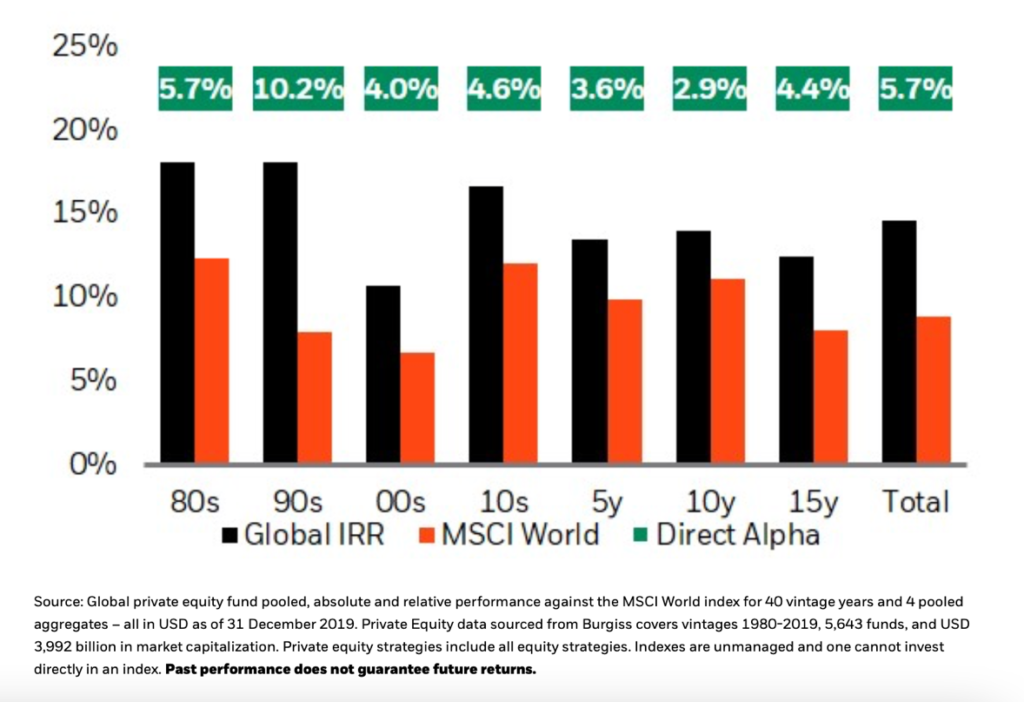

Historical evolution of the Private Equity Industry over the past 4 decades

The above graph, published by BlackRock institutions, measures the outperformance by the private sector of the public sector in percentage. The graph shows that the PE sector has had a strong performance in all four decades. The lowest figure, the 10-year outperformance, resulted from an expansionary monetary policy by the Central Banks, fueling public sector investments. According to the report published by BlackRock Institutions in 2020, one of the key takeaways represented by this graph is that “Private Equity outperformance over the MSCI World index is consistently positive, and reports a lower decline than public markets during periods of high market volatility.”

To measure the outperformance, three main indexes were used:

- Global IRR: is an index measure of the Internal Rate of Return of Private Equity companies. The IRR is a metric to estimate the profitability of a potential investment in financial analysis.

- MSCI World: a broad and global equity index that large and mid-cap equity performance across all 23 developed markets.

- Direct Alpha: a calculation of the rate of excess return directly based on the PE portfolio’s cash flows and the time series of returns from the reference benchmark.

Present and Future of Private Equity: Conclusion

To sum up what we analysed, we can start by saying that nowadays, Venture Capital companies are investing in startups all over the world to make use of global opportunities: Silicon Valley, the former hotspot of the VC industry, only makes up a small percentage of worldwide VC activity.

While VC funds used to have a typically passive approach that still prevails today, there are pressures towards more activist approaches in an attempt to improve the portfolio companies.

Regarding the overall Private Equity industry, in 2021 the global PE transaction volume reached approximately $1.2tn, and in the same year PE firms exited 3895 investments, with a total deal value of about $665bn in 2021, thus marking record values.

The number of SPACS, however, has slowed down in 2021, with several enforcement actions of the Securities and Exchange Commission against them.

Considering the current economy, possible interest rate increases due to inflationary pressures could lead to less available credit to support leveraged buyouts and a worsening of the economic environment due to the Ukraine-Russia conflict could reduce the number of investees and lead to a buildup of dry powder. As seen with the financial crisis, in times of high stock volatility IPO’s and other exits may be postponed and VC’s may reduce their exposure on later-stage companies.

The Private Equity industry is however projected to continue to grow, with an increased focus on ESG investment, and an increased importance placed onto the relationship between portfolio companies and their PE providers. According to a report published by Deloitte, a base case scenario forecasts global PE AUM to reach $5.8tn by 2025.

Sources

https://www.blackrock.com/institutions/en-us/insights/investment-actions/private-equity-evolution

https://www.crunchbase.com/organization/j-h–whitney—co

https://en-academic.com/dic.nsf/enwiki/10039901

https://www.builtinchicago.org/blog/ask-vc-how-do-they-decide-whether-take-active-or-passive-role

https://individuals.voya.com/pomona-investment-fund/private-equity-why-secondaries

https://pitchbook.com/news/articles/2021-record-year-us-venture-capital-six-charts

https://www.bloomberg.com/professional/blog/spacs-were-hot-in-2020-and-are-hotter-now-heres-why/

https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/other/mb200510_focus02.en.pdf

Comments are closed.