As ESG-related investments strongly increase their importance, so do ESG evaluation metrics that can prevent greenwashing practices. This article provides an overview of the main ESG Evaluation metric provided by S&P Global Ratings, later describing why such evaluation method should be taken into consideration in Private Equity funds and their investment strategies. It will then evaluate whether ESG really makes a positive difference on society by diving deep into an excursus on greenwashing, so to better understand the phenomenon and to explain how a lack of measurement can affect investment performance. Both topics of ESG and greenwashing are becoming increasingly relevant nowadays as they are closely linked to wider country-level sustainability goals and investment returns targets for Private Equity firms.

ESG Evaluation

ESG Evaluation by S&P

In 2019, to help harmonize ESG information and allow companies and their investors to better understand the ESG risks and opportunities on their horizons, S&P Global Ratings launched the ESG Evaluation: a forward looking, long-term opinion of a company’s ability to effectively manage future risks and opportunities.

“The ESG Evaluation is thoughtful, data-driven yet embedded in a strong and deep understanding of the credit. It’s very powerful to highlight this has been drafted from the standpoint of an analyst who has had access to management and knows the business. The consideration of Preparedness is key because it helps us understand how the bank is prepared to bring a transition to 2030 to 2040 to 2050.”

Michael Eberhardt, Director at BlackRock

With a company’s permission, the ESG Evaluation uses responses from the S&P Global Corporate Sustainability Assessment (CSA) and is further supported by deeper engagement between the Ratings’ Analysts, company/bank management and a board member. Each ESG Evaluation comprises two inputs: the ESG Profile and Preparedness opinion.

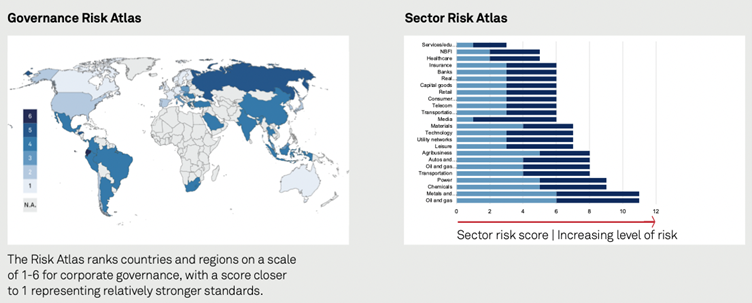

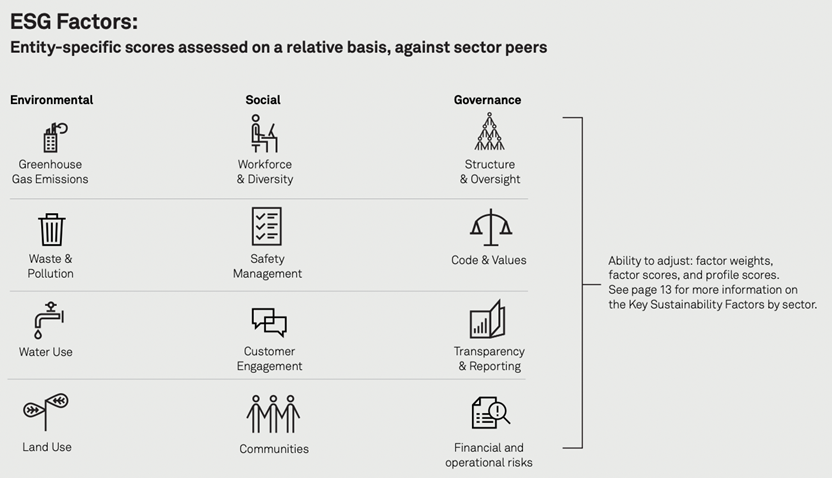

The ESG Profile score combines S&P Global Ratings assessment of three Profiles: Environmental (30%), Social (30%), and Governance (40%). This type of information is obtained with the Corporate Sustainability Assessment (CSA), an annual evaluation of companies’ sustainability practices covering 10,000 companies from around the world. It is imperative to specify that 40% of the ESG Profile is driven by the macro sector in which the entity operates, as reported in S&P’s Sector Risk Atlas (Exhibit 1 and 2).

On the other hand, the Preparedness opinion is a qualitative view of a company’s ability to anticipate and adapt to various long-term disruptions. To develop it, S&P Global Ratings analysts meet with the company’s senior management and a board member to assess their awareness and readiness about emerging trends and potential business disruptors (Exhibit 3).

Exhibit 3: Preparedness Evaluation Criteria

Once the ESG Profile Score and the Preparedness opinion have been defined, they are combined into an overall ESG evaluation score, on a 100-point scale.

Why PE investors should care about ESG Evaluation

Shareholders and market investors’ attention is indeed rising towards ESG, especially thanks to precise metrics such as the S&P ESG Evaluation, which allows institutional players to quantify the ESG attitude of a firm. But is investors’ concern on such ESG metrics well-founded or is it a mere trend? Data and research seem to show that ESG does concretely generate higher value for firms, including Private Equity owned ones. Interestingly enough, PE owned firms have been historically less concerned about ESG metrics, partly because they do not have the same need as public firms to strictly attain to sustainability-related goals. However, although it might not have as strong of an impact as in publicly held firms, ESG valuation does play a significant role in value creation of firms in PE too. Three are the main ways through which ESG generates value: increasing revenue, decreasing costs, and finally decreasing risks at the moment of sale of the firms owned by the fund.

Main methods through which ESG Evaluation impacts overall target firm operations

Regarding the first category, increasing revenue, as argued by McKinsey (2020), adopting an ESG strategy is a new source of value-added and competitive advantage towards competitors that are not ESG oriented. This happens because green strategies can attract new, more sustainability-aware customer targets. The logic is that, by increasing ESG, the more respondent customer groups would shift their consumption towards the highest ESG firms. This would increase revenues and, ceteris paribus, margins for PEs owning ESG-oriented firms.

Moving on to the second aspect, one could argue that ESG-related initiatives might also increase a firm’s margin by potentially decreasing costs of production. As firms employ cleaner methods of production, waste is reduced, and costs are saved. Also, employing greener strategies, might lead to cost savings in terms of inputs of production. For example, using clean energy rather than fuel decreases variable costs for each unit produced, as cheaper alternatives that had not been previously considered are now used. According to McKinsey’s research (2020) operating expenses can drop by up to 60% when employing cleaner production methodologies.

In third instance, focusing on ESG-oriented firms allows PE investors to reduce exit risks, potentially increasing profitability and returns. As a matter of fact, two are the main risks associated with investing in firms with a low ESG Evaluation score: transition and litigation risks. The former encompasses the societal shift of preferences towards more climate-friendly businesses. The argument follows: if the future really holds sustainability as one of its key pillars, PE funds which have invested in “polluting” firms will have a harder time selling those assets, thus obtaining to a lower return. On the other hand, by pre-emptively investing in firms with an above average ESG score, a fund would experience more appetite for its assets would therefore be able to sell them at higher valuations, with higher returns.

The second main risk that investors would avoid by investing in high score ESG businesses consists in litigation risks, defined as the risk of being involved in legal actions deriving from false claims about sustainability commitments. Litigation cases on climate-related topics for public firms have almost doubled from 2017 and this has happened both because more firms have been making more fake claims on their sustainability strategies and because more entities have been looking into this topic to litigate fake claims. Hence, when acquiring a company, due diligence should not just encompass business elements but also focus on the green ones, so to avoid potential future litigation that would harm the exit value of the asset and reputation of the PE fund.

To sum up, higher revenues, lower costs, and lower risks are three main reasons why investors in PE should care about ESG valuation, but there are many other reasons why investing in a firm with high ESG Evaluation is a clever idea. Some invest in socially responsible firms for the so-called “warm-glow effects”, or effect of feeling good about one’s investments, which is a non-pecuniary aim for ESG investing. ESG has become more important in public firms, but many managers in Private Equity are becoming aware of the importance of ESG too. For instance, 72% of Private Equity professionals responding to a recent survey by PwC state that they analyze ESG valuations during due diligence period before entering in buyout agreement. But is this growing attention to clean investments concretely impactful on tomorrow’s sustainability? To some extent it is, but some factors may erode part the positive effects that come with ESG investing, for example the practice of greenwashing.

Greenwashing

What is greenwashing?

ESG funds can make a substantial impact by reallocating capital away from companies that do not take part in the net-zero transition. Yet, the risk that companies consciously or unconsciously misrepresent the sustainability of their financial products and services, also known as greenwashing, poses a severe risk to sustainable transformation. The term greenwashing was coined in 1986 by Jay Westerveld, an American environmentalist, in reaction to the hypocrisy of a beach resort. Although the resort was building new tourist bungalows over threatened coral reefs, it left notes in hotel rooms asking guests to reuse their towels to help protect the environment.

Today, there are even stronger financial and marketing incentives for firms and managers to make assertions on sustainability practices. Greenwashing was born and continues to be persistent because companies have spotted a commercial opportunity amid rising awareness of ESG issues among consumers. Indeed, according to Nielsen 66% of US customers are willing to pay higher prices for environmentally friendly products. Furthermore, in Europe, the Consumer Market Monitoring Survey found out that 78% of customers consider the environmental impact of products to be “very important” or “fairly important” factors when making a purchase.

Types of greenwashing

Typically, it is possible to identify two types of greenwashing in the market. The first one is related to corporate greenwashing or more simply investments in companies that practice greenwashing themselves. For instance, companies promote environmental credentials for their products and services that are considerably inflated or even contrary to their performance. Anyhow, simply investing in “virtuous firms” does not automatically produce any real impact.

The second type is portfolio greenwashing carried on by the finance industry. Indeed, asset managers may assert that their funds generate a positive impact on the environment when instead they are not managed in a way that is coherent with producing such impact. Hence, investment managers may try to convince investors that their funds help to protect the environment when they do not. Consequently, the risk is that long-term climate promises will not have any real short or medium-term impact.

Measuring greenwashing

Measurement is about being able to compare impact, however commonly used portfolio construction systems fail to provide consistent impact objectives. The great majority of institutional funds that claim to have a positive impact on climate are exposed to evident greenwashing risks, mainly because they flaunt attractive climate metrics at a portfolio level through the implementation of flawed mechanisms. Moreover, achieving significant portfolio-level carbon metric improvements is attractive from a marketing standpoint, but it does not necessarily translate into meaningful real-world impact. Indeed, we observe a significant proportion of stocks that benefit from such investment thesis despite deteriorating climate performances.

On this topic, the economist Laura Starks surveyed over 400 institutional investors in the US about their climate risk perceptions and management strategies. Most investors surveyed believe that climate risk is both underpriced in financial markets and financially material to their investment decisions.

An example of greenwashing

In 2021, DWS Group, an investment unit in one of Germany’s biggest banks, was accused of overstating the scope of its sustainability practices. It is the group’s former head of sustainability, Desiree Flixer, which first alleged that the group was misleading clients and investors by asserting that 50% of its assets under management were dedicated to ESG-investing. She claimed that the group’s ESG risk management system was not adequately used and employed outdated technology, and thus the impact measurement standards applied were unreliable. When the news broke, DWS’ shares sank by 14%. To this day, the group is still being investigated by the U.S SEC and Germany’s BaFIN to measure the accuracy of Flixer’s greenwashing accusations.

It is not the first time that an influential firm is implicated in such an affair. In September 2015, Volkswagen group was accused of rigging ‘Clean Diesel’ vehicles to cheat carbon emission tests. On the day the news broke, the company’s shares fell by 22% and, as of 2020, it has paid over €31 billion in associated fines and settlements.

Overcoming greenwashing

Recently, several scholars have researched sustainability standards to understand which tools are the most appropriate to measure impact. Cohen, Gurun, and Nguyen (2021) researched green patenting across firms and checked whether capital allocation based on ESG factors is aligned with incentives to innovate. They noticed that many companies ranking poorly on Sustainalytics’ environmental rating generate higher quality green patents than do highly rated companies. Hence, they claim that sustainability-related valuation metrics are inaccurate. Opp (2020) also asserts that investments in firms that operate in traditionally highly polluting industries but use relatively cleaner technologies than their peers, help to avoid more emissions than investments in low-polluting industries. In this regard, investing to help high-pollution industries to decarbonize can be perfectly coherent with the mandate of being socially responsible.

To curb greenwashing new EU-level standards must be put in place. For now, regulators should avoid encouraging green labels based on regulations that in no way safeguard clients from greenwashing risks, as is the case with the likes of the EU Paris-Aligned Benchmark Regulation. In this sense, the Sustainable Financial Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) of March 2021, should help investors better decipher which investment funds employ the most stringent ESG standards. The EU has taken additional steps by conducting greenwashing examinations. For example, in January 2021, the European Commission collaborated with national consumer agencies to investigate the corporate websites of European firms. It found that 42% of these companies’ “green” marketing claims were overstated, false, or even fraudulent.

State-of-the-art technology can also facilitate the monitoring and reporting of ESG practices. For example, blockchain can transform sustainability reporting and verification, helping firms manage, prove, and boost their performance while enabling investors and clients to make better-informed decisions. Moreover, it has the power to improve corporate reporting by permitting the independent sourcing authentication of company performance beyond the self-reported data presently provided. When combined with third-party measurement and verification systems, this would present independent and reliable information to assist a firm’s management and investor decisions, thus bolstering market efficiency and providing incentives to drive the sustainable transformation. Self-reported data can represent a source of asymmetric information between companies and investors if there is no independent authentication and benchmarking of the values disclosed. Hence, a system based on the blockchain could solve this problem. The first example of this can be traced in the fashion industry where a task force led by Federico Marchetti (founder of Yoox) is working to create a digital passport for fashion garments tracking how these are projected, produced, and distributed. It is still a long way to go, but finance should not underestimate the importance of discerning green and greenwashed as well.

Authors: Giacomo Nicoli, Ginevra Forcellini, Filippo Zocco, Céleste Vildé

Editor: Mauro Spadaro

Sources

- AIQ Editorial Team. (2021, May 26). Green is not always clean: Rising tide of greenwash brings risks for investors. Aviva Investors. Link

- Beaujon, A. (2021, August 27). DWS accusé de greenwashing: coup de semonce pour tous les gestionnaires d’actifs. Challenges. Link

- Cheasty, G. (2019, December 5). Integrating ESG risk into a risk management framework. Deloitte Ireland. Link

- Comfort, N., Ainger, J., & Schwartzkopff, F. (2021, October). Fund Managers Brace for Correction as Greenwash Rules Go Global. Bloomberg. Link

- Delevingne, Gründler, Kane, & Koller. (2020, February 12). The ESG premium: New perspectives on value and performance. McKinsey Sustainability. Link

- ESG Risk, our investment risk metric. (n.d.). Etica Sgr. Link

- Ferguson, M., Martin, N., Burks, B., Bendersky, C., de la Gorce, N., & Wright, H. (2019, April 10). Environmental, Social, And Governance Evaluation. S&P Global. Retrieved December 24, 2021, from Link

- Flood, C. (2021, November 8). Regulators step up scrutiny over investment industry ‘greenwashing.’ Financial Times. Link

- Fowlie, M. (2021, December 10). Climate Finance: The loopholes that are causing greenwashing. Energy Post. Link

- Henisz, Witold, Tim Koller, and Robin Nuttall. (2020, November). Five Ways That ESG Creates Value. McKinsey. Link

- Iovinella, M. R. (2021, October 31). Moda, un passaporto digitale per certificare il fashion sostenibile. Wired Italia. Link

- Janssen, J. (n.d.). Six key challenges for financial institutions to deal with ESG risks. PwC. Link

- Private Equity ’S ESG Journey: From Compliance To Value Creation. (2021, December 10). PwC. Link

- Tyson, J., & Tyson, J. (2021, July 21). Corporate “greenwashing” poses growing threat to ESG goals: report. CFO Dive. Link

- Gambetta, G. (2021, November 8). Swiss financial regulator in push to tackle greenwashing. Private Funds CFO. Link

- Goltz, F., Amenc, N., & Liu, V. (2021, August). Doing good or feeling good? Detecting greenwashing in climate investing. EDHEC Business School. Link

- Gourntis, K. (2021, September 16). Who’s afraid of greenwashing? New Private Markets. Link

- Gunia, A. (2021, September 20). Thinking of Investing in a Green Fund? Many Don’t Live Up to Their Promises, a New Report Claims. Time. Link

- Impact investing risks being undermined by greenwashing, says Robeco. (2021, May 28). Institutional Asset Manager. Link

- Ricketts, D. (2021, August 31). DWS greenwashing probes shift fund industry into high alert. Financial News. Link

- Smith, T. (2021, September 23). Show us the colour of your money – greenwashing in sustainable finance. Travers Smith. Link

Comments are closed.