by Giacomo Baldassarre, Michele Bing, and Raul Li

Introduction

The decade following the Great Financial crisis benefited from low interest rates and abundant credit availability, and, consequently, valuations soared consistently. As the era of cheap money slowly vanished in early 2022 due to central banks intervening in an attempt to tame skyrocketing inflation by setting high interest rates, an economic slowdown took hold as the outbreak of the war in Ukraine exacerbated the disruption of global supply chains, already damaged by the Covid-19 pandemic, and induced higher commodity prices. Such economic phenomena resulted in a barbell-shaped private market fundraising pattern for 2022.

Overall, the fundraising totals withstood the economic turmoil, registering a loss of $100bn from the all-time highs registered in 2021, amounting to $727.8bn. Denominator issues caused a domino effect for managers as funds were taking longer to reach a final close as a result of various factors: smaller tickets, sharper selectivity, and budget constraints. Consequently, capital flowed to a much smaller number of funds (1,520), the lowest level since 2017, with respect to 2,278 special purpose vehicles reaching a final close in 2021. As for 2022 fundraising strategies, buyout funds captured 52% of all capital raised, whilst Venture Capital (VC) accounted for 48% of funds closed.

Private Equity Fundraising: What, Who, and How?

In its simplest form, Private Equity (PE) fundraising is the process by which PE firms raise capital from Limited Partners (LPs) to ultimately invest in privately-held companies or take public companies private.

LPs are typically segmented into two distinct groups:

- Institutional Funds

- Fund of Funds (e.g. Adams Street Partners): Investment funds that invest in other PE funds, rather than directly in target companies.

- Pension Funds (e.g. PSP Investments): Retirement plans that are sponsored by the employers.

- Sovereign Wealth Funds (e.g. Abu Dhabi Investment Authority): Government-owned investment funds.

- Endowments (e.g. Harvard Endowment): Capital from educational institutions.

- Foundations (e.g. Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation): Funds set up by non-profit organisations.

- High Net Worth Individuals (e.g. Michael Dell) or Family Offices (e.g. Soros Fund Management), that manage the assets of those individuals.

The fundraising process can take several forms, depending on the type of LPs and their varying preferences, especially with regard to risk tolerance. In fact, PE firms can use the following channels to raise capital from fundraisers:

- Direct Outreach: Traditional approach in which the PE firm reaches out directly to investors.

- Placement Agents (e.g. Evercore Private Funds Group): Third-party agents with an extensive network and contact of potential investors that specialize in raising capital for alternative investments.

- Online Platforms (e.g. AngelList): Modern electronic platforms that require investors to meet certain financial criteria and may charge fees for access to PE investments.

- Secondary Markets: Early exit path for existing investors to other new investors.

- Public Offerings: in some cases, PE firms may list its shares on a stock exchange or conduct an Initial Public Offering (IPO) to raise a more permanent type of capital.

During the entire fundraising process, PE firms must remain in close contact with their investors in order to avoid any information asymmetry and guarantee transparency into their investment strategies and performance. In any case, PE fundraising is an extremely complex and highly regulated operation that requires significant expertise and resources. The expertise mentioned here refers to the financial expertise to interpret the market and structure potential deals, legal expertise to navigate through the regulatory landscape and ensure compliance, business expertise to identify refined business plans, and marketing expertise to develop relationships of potential LPs. On the other hand, the resources are in terms of personnel and capital, which its requirements can vary regionally and from fund to fund, mostly depending on the local regime and target size of the fund/deals.

Private Equity Fundraising Analysis by Region & Sector

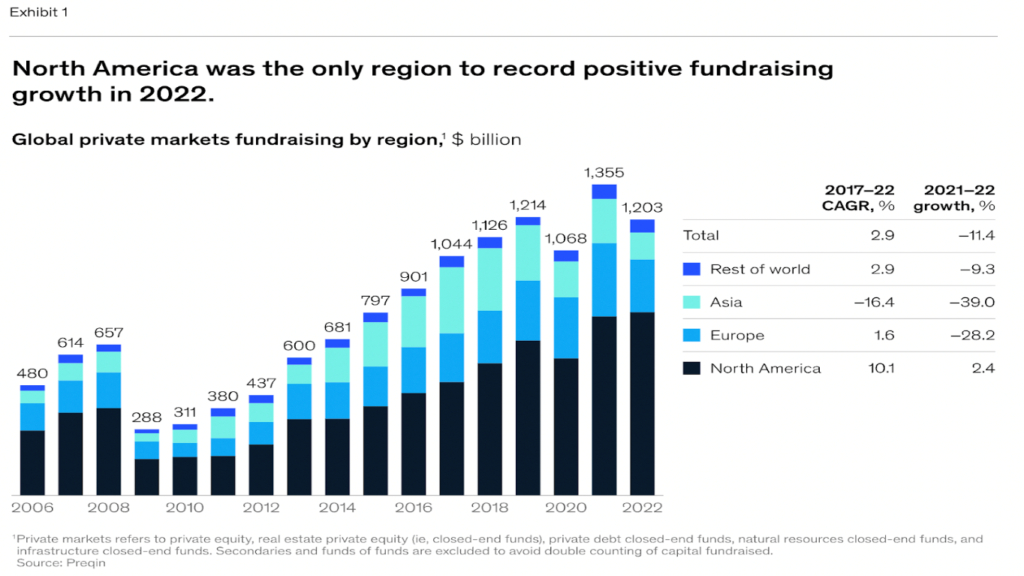

The steep decline in fundraising was most evident, as of 2022, in Europe and Asia, raising $59.25bn and $64.01bn respectively, with Asia-Pacific funds surpassing Europe in capital raised. North America funds proved to be rock solid, registering five times more capital raised with respect to Europe, accumulating $338bn and experiencing a positive expansion.

PEA performed worse than other private asset classes, resulting in negative returns, as of September 30, 2022, for the very first time since 2008. On the other hand, natural resources strategies, bolstered by inflated commodity prices, achieved comparatively robust performance for two years in a row. Despite the downturn recorded for fundraising and investment performance, the industry experienced a stable growth pattern, highlighted by the fact that AUM increased to $11.7 trillion as of June 30, 2022.

PE and VC, as historic trends suggest, approximately contribute for 50% of global private capital fundraising, and this has not changed in 2022. The VCindustry had to cope with the initial stock market downturn due to the greater exposure to risk and overall speculative nature inherent to VC investments.

As a consequence, VC firms adopted a more precautious approach, by withdrawing potential investments and by applying stricter strategies to their portfolio companies. In defiance of the challenges of the industry, related to dealmaking and valuation, capital raised in 2022 by VC funds constituted 87% of 2021 VC financing.

PE firms, typically endowed with larger pools of capital, were presented a unique opportunity, as the number of target companies with lowered valuations available for purchase increased. Indeed, as of September 2022, PE funds raised more aggregate capital with respect to their VC counterparts and all other fund types.

Another major consequence of market uncertainty in 2022 was the shift in LP preference, highlighted by two main indicators: the share of funds over $1bn has increased and first-time fundraising activity has drastically dropped. The first factor indicates that LPs are endorsing managers with more expertise to a greater extent due to market volatility.

The second indicator draws attention to the radical decline in the number of first-time funds that have raised in 2022, which was 293 compared with 824 in 2021, a complete tumble, considering the fact that every single year since 2016 more than 800 first-time funds raised capital.

Furthermore, total private capital dry powder took a massive nosedive from a peak of $3.7tn in 2020 to $3.2tn halfway through 2022. As dealmaking is not as frenetic as it used to be and investors’ uncertain sentiment is slowing down fundraising efforts, funds, due to slower momentum, are prioritizing their already existing capital over raising additional funds.

Factors & Challenges Affecting Private Equity Fundraising

- Market Conditions

As previously mentioned, private markets have enjoyed strong tailwinds since the depths of the global financial crisis, with low interest rates, high credit availability, and consistently rising valuations. Each year since its inception, even in 2020, when activity stalled briefly during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, private markets hummed again in the second half. In almost every regard, 2021 was an exceptional year but it was not a trend breaker. Markets climbed higher still, awash with central-bank-induced liquidity. In the first half of 2022, central banks fought roaring inflation by sharply raising interest rates, and public market valuations cratered. In the private markets, first-half deal activity softened but subtly so, nearly matching the record-setting pace set in 2021. Fundraising results differed notably across geographies, more so than in previous years. Private market fundraising in North America increased by a modest 2 percent year over year but declined in Asia and Europe by 39 percent and 28 percent, respectively. Since 2017, fundraising in Asia has declined 16 percent per year, driven primarily by reduced investment in China. In 2017, for example, China represented 83 percent of fundraising in Asia, a share that dropped to 34 percent in 2022. In Europe, an 11-year run of fundraising growth ended, largely due to geopolitical instability and broader macroeconomic challenges, including volatility in foreign currency exchange rates. A strengthening dollar accounted for a material portion of the dollar-based decline in fundraising in non-US markets.

- Geopolitical Risks

Last November at the G20 conference, Presidents Joe Biden and Xi Jinping pledged to stabilise the tense U.S.-China relationship. Thus far, an easing of tensions has been elusive. The purpose of Secretary of State Blinken’s trip that was cancelled in the wake of the incidents involving Chinese spy balloons earlier this month was to establish a floor in deteriorating U.S.-China relations. The postponement of Blinken’s trip was not welcome news for Beijing, whose focus for 2023 is a domestic economic recovery, rather than international relations. In contrast, the U.S. administration may seek some improvement in relations so the Blinken trip could be rescheduled. Some Flashpoints that could escalate tensions:

- If Chinese companies are found to be providing significant aid to Russia’s war effort, it could spur calls for secondary sanctions on China. It looked like China had largely refrained from providing material help, but a few recent press reports suggest there may be more military equipment sales than previously thought, in violation of Western sanctions.

- How far-reaching the administration’s forthcoming executive order on U.S. investment in China will be is yet unknown. The widely held expectation is that the order will limit investment in a narrow range of sensitive industries that have military applications (such as A.I. and certain high-tech equipment). Yet, it’s possible that a broader ban on U.S. investment in Chinese firms emerges alongside legislative efforts to ban TikTok.

- The market appears to be pricing in hope that the intensity of the Ukraine war subsides and perhaps even moves toward a negotiated resolution, potentially ending military hostilities and limiting risks of re-escalation. It seems likely that any path to end the fighting would involve resolving Ukraine’s claim to Crimea, which was seized by Russia in 2014. Any move by Ukraine to retake that territory may be Putin’s red line. Should Ukraine cross into Crimea after continuing to push through Kherson, the risk of escalation by Russia could rise.

An escalation could take the form of further large-scale attacks on civilian infrastructure or restrictions on export capacity through military constraints on the use of Black Sea shipping routes. But even more worrisome, escalation may take the form of using prohibited nuclear, biological, or chemical weapons to defend what Russia sees as Russian territory, pre-emptively striking arms shipments to Ukraine by members of NATO, or even purposefully or inadvertently drawing neighbouring countries into the conflict with either intentional or unintentional military strikes.

What we do know is that a long history of drawn-out conflicts involving oil producers tends to affect energy supply and prices. We initially observed it in 2022, but its full impact has not yet been realised. Today, oil tankers carrying Russian oil that had been going to Europe must now ship their cargo farther to have it reach customers in India and China. These longer voyages are tying up oil tankers for longer timeframes and creating a global shortage of available ships. At the same time, China’s demand for oil is rebounding from below trend levels. If the transportation shortage translates into tighter supplies or higher prices it could slow global growth and lift inflation.

Outlook

VCs that backed businesses are no longer able to draw in further capital from their existing funders. Multiple reasons are cited, including funds concentrating their dry powder on their most promising assets which still require significant capital before they reach break-even. If these ‘stranded’ businesses slow down their growth rate and focus more on preserving cash, they in effect become less suitable for the high risk/high return profile of a VC portfolio and more appropriate for PE backers. Those exits could be in full, or partial where PE takes a stake alongside VC in what is known as a growth capital investment. The latter is attractive for the incumbent shareholders as it still gives them access to future growth and upside and helps them realise some returns, while for the growth capital investor they have a lower exposure and other parties will share the burden of possible future capital needs. PE typically takes majority stakes so we expect most of these deals will involve a full exit by the VC firm.

Sources

https://www.investeurope.eu/media/1320/130524-context-paper-for-oecd.pdf

https://dealroom.net/faq/pe-fund-structure

https://www.ey.com/en_gl/private-equity/pulse

Editor: Marco Peyre

Comments are closed.