By Joerg Friedl

In early January, legacy mega fund KKR announced its purchase of a majority stake in the extensive music rights back catalogue of Ryan Tedder for its New York based Dislocation Opportunities Fund. The catalogue of the One Republic singer-songwriter includes 500 songs, which he has penned for superstars such as Beyoncé, Adele, Paul McCartney and Stevie Wonder. While the deal value was not officially disclosed, it is believed to be around USD 200 million. Although this is just the latest deal in a frenzy of other high-profile nine-figure purchases, it marks the first such deal by an established private equity giant. This raises the obvious questions about the nature of the value proposition upon which the current rush into music rights is built.

Some might argue that music is by no means the first alternative asset class that is eyed by private equity funds not solely for the decent risk-return profile, but possibly also for the simple reason that it is fun to own them. Similar exotic investments were and are made into the professional sports sector. CVC Capital Partners famously bought Formula 1 in 2006 for USD 2 billion and subsequently sold to Liberty Media it for a hefty USD 8 billion in 2017. In that spirit more recent deals included outright buyouts of prime European football clubs such as AC Milan by Elliot Management Corporation in 2019.

So possibly the appeal of owning music rights is conceptually the same as with these investments in the sports sector: trophy assets that are owned by individuals – oligarchs in sports and singer songwriters in music – that are not well versed in adequately managing their assets. In other words, the current owners are leaving money on the table and sophisticated private equity investors such as KKR are keen to change that for their benefit.

However, the story with music rights seems to be more complex than that. To understand why the music market is so feverish at the moment, we must appreciate the factors which make music royalties in the streaming age a nearly perfect match for alternative asset funds.

Marty Bandier, the former CEO of Sony/ATV Music Publishing, is reported to have once said: “Music and booze are the only two consumer industries that flourish when people are both happy and sad”. While this is clearly a non-authoritative simplification, it does highlight a fundamental reason why the intellectual property rights related to music catalogues are currently one of the hottest alternative asset classes: music rights and their royalties are essentially a fixed income structure, however they are largely unaffected by the macroeconomic environment. People tune in to music during a boom just as they do during a recession. In other words, the cash flows from royalties are exceptionally stable. Further, unlike as with movies, music publishing rights in most cases are owned by just a small set of individuals. This fundamentally eases the process of acquiring, controlling and effectively monetizing them. These natural characteristics of music related royalties raise the obvious question why the market for music rights is booming now and has not done so earlier.

Indeed, investments in music publishing rights and even fixed-income structuring of such royalties are nothing novel per se. In 1985, Michael Jackson, the king of pop, famously paid USD 47.5 million (equivalent to 116 million in 2021) for the rights for about 250 Beatles songs and in 1997 David Bowie offered “Bowie Bonds” to retail investors which would let them participate in his music’s future royalty earnings. Nevertheless, these targeted investments were exceptions to the rule of artists and songwriters retaining the rights themselves or selling them to big music labels which simply viewed them as products to be sold.

So, what has changed? There have been two disruptive forces: widely and cheaply available streaming technology and the very low interest rate environment of the last decade.

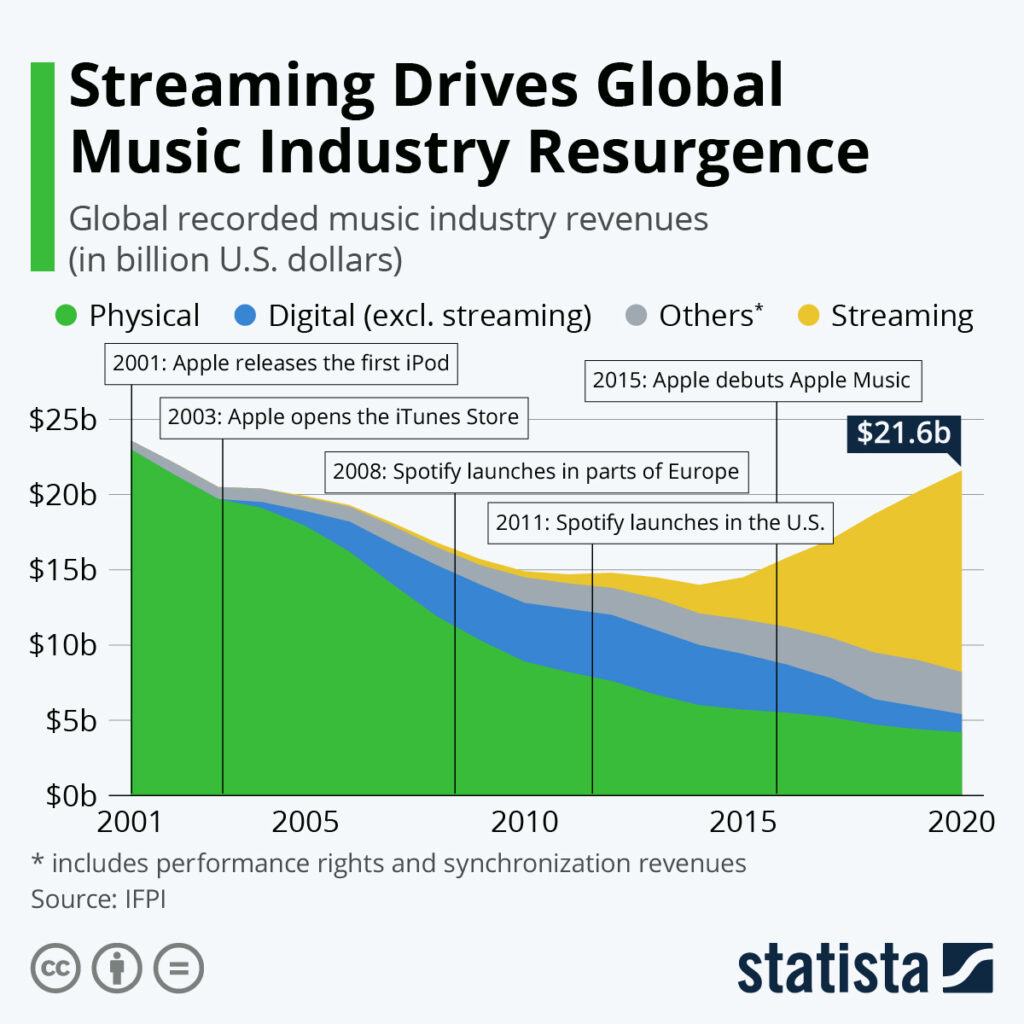

First, technological advances enabling the low-cost distribution of vast music databases to a global consumer base had a very deep impact on the music publishing rights sector. Traditionally, the cash flows derived from songs have been heavily frontloaded: a new album would generate most of its revenues early on in its chart fueled hype phase and then enter a phase of supposedly eternal decline. With such unattractive future discounted cash flows, it is not surprising that the music industry used to be a short- to medium-term focused buyer’s market.

The appearance and widespread adoption of music streaming has changed both, the return generation model for their owners and the valuation of music related intellectual property. In effect making music-based fixed income structures more bond-like.

What used to be heavily frontloaded investments, now provide very stable and evenly distributed cash flows. Only a few people would buy a classic hit on iTunes or even in a brick-and-mortar CD store after being exposed to it in a Netflix show. However, billions of users decide to stream such songs on a regular basis, giving old songs a second life and potentially turning them into valuable evergreens. Furthermore, the data provided by streams and downloads has made it easier to assess the value of songs by enabling reliable forecasts of their future earnings.

Second, while the cash flows of music royalties have become more bond-like due to the streaming revolution, the depressed interest rate environment has given music rights an additional boost as an alternative investment class. The very low yielding debt climate has forced institutional investors to search for viable alternatives to fixed income products. Such fixed income streams are necessary to enable institutional investors such as pension funds, foundations and insurances to efficiently plan and cover their long-term cash flow needs.

Consequently, catering to these demands of their investor base and facing dramatically revised evaluations of the underlying publishing rights, it is no surprise that young specialist funds such as Hipgnosis or established private equity giants such KKR have found a taste for the promises of stable and long-term excess returns of music rights as an alternative investment class. The main focus of this activity is on extensive back catalogues of mostly foregone hits. This scale approach is inherently rational, considering that every investor should aim for the greatest degree of portfolio diversification feasible. In other words, since nobody can know which oldie will become the next TikTok sensation, it is optimal to own as many as possible.

This scramble by specialist funds, legacy music labels and private equity players for typically very rare but lately highly valued quality catalogues has led to sky-high prices. In addition to KKR’s Ryan Tedder deal mentioned earlier, another prominent recent example is the sale of Bob Dylans entire back catalogue to Universal Music for an undisclosed nine-figure amount north of USD 300 million. Legendary repertoires such as Mr. Dylan’s will generate sales for decades to come when his songs are streamed, played on the radio, and used in films, advertising and social media.

While there is normally neither full transparency on the pre-deal returns generated by such catalogues nor on the sales prices, sector insiders confirm valuations based on 20 to 25 times annual revenues. Such valuations, strong scarcity and typically close personal control of the targeted assets is evidence that the current music publishing rights market is a seller’s market.

In this context, one might rightfully wonder why (ultra)-high-net-worth artists are increasingly willing to sell their income generating legacy to third parties. Besides the obvious monetary incentives to cash-out on their life’s work – especially during times of foregone touring income due to COVID-19 – most artists are also driven by at least three other incentives. First, giving the nature of a seller’s market, musicians find themselves in the unique position to receive a great amount of value while still being able to dictate custom contracts. An example of a not uncommon customization of a deal could be that an artist wishes to retain some stake in the catalogue, either as a total percentage or as full rights for a specific geography. Second, artists find themselves in the rare but for them valuable position to be able to select the future manager and distributor of their musical legacy on their own terms. Lastly, considering that most deals involve catalogues of times past, the respective musician might have the well-founded hope that a buyer with expert industry knowledge and a strong network can grow new opportunities for their music.

These expectations by the selling artists are increasingly met by the different players in the music rights market. Accordingly, besides the price, buyers increasingly wish to highlight their strong network and industry knowledge to convince financially mostly independent A-list individuals to deal with them. Thus, although all players hunt for the same sought-after exotic assets, their strategies and propositions towards the artists can differ fundamentally.

The three main investor types of this currently fiercely competitive market are specialist funds, established private equity players and music labels.

The ongoing music gold-rush was started by specialist funds marketing music rights to private and institutional capital as an alternative asset class. Nearly all those specialist funds have been founded under the clout of existing music industry players. Noteworthy players include: Round Hill Musical Royalty Partners which owns over 100,000 titles and has collected USD 763 million in 3 funds, and PrimaryWave music fund which has bought a catalogue containing Johnny Cash in early January 2021.

However, the one UK based fund that has increased the heat like no other in the recent music rights craze is Hipgnosis Songs Fund. Founded in 2018 by Beyonce’s and Elton John’s former manager Merck Mercuriadis, Hipgnosis stands out due to its rapid growth, indiscriminate spending and strong institutional investor base that includes the insurer AXA, Schrodinger and the Church of England. Since its inception, the open-end fund has spent GBP 1.2 billion on a buying spree for catalogues containing 58,000 songs which include eight of Spotify’s Top-25 streamed titles of all time. Another outstanding characteristic of the fund is the very active way in which it tries to promote its songs by having them included in films, television shows and streaming playlists. Hipgnosis has in the past confirmed that the fund has paid an average multiple of 14.76 of annual revenue for its catalogue acquisitions.

The activity of niche funds such as Hipgnosis and PrimaryWave has caught the attention of established private equity players. As briefly mentioned at the beginning, mega fund KKR has firmly re-entered the music sector. After having purchased the majority stake in songwriter Ryan Tedder’s extensive catalogue, KKR announced it would partner up with BMG, one of the world’s largest music firms. The goal of the cooperation is to pursue major music label and catalogue acquisitions during the industry’s consolidation boom. Interestingly, KKR used to be an original majority stakeholder in BMG when the firm was relaunched in 2008 but later sold out to its partner Bertelsmann, the German media group, in 2013. Today’s cooperation with BMG is KKR’s most significant offensive into music in the last decade. As part of the partnership KKR will give BMG the financial muscle it requires to compete for the best music assets in a year in which more than EUR 1 billion of catalogues are expected to be up for grabs. The deal is neither set up as a joint venture nor as a direct investment. Instead, the two firms will buy music assets together and split the profits in the future.

When it comes to considering music publishing rights as an asset class to invest in instead of solely a product to be sold, the last group of players, namely the big legacy music labels, can be considered as laggards. Notwithstanding that they certainly reap the fruits of their already extensive catalogues and have by now entered the competition forcefully. Warner Music and Universal Music are estimated to both earn royalty revenues of around USD 1 million per hour, day and night. Further, Warner Music recently made a royalty payment settling agreement with ByteDance, the owner of TikTok, thus already anticipating social media as the next big source of growth for the royalty business, acknowledging the growing saturation of the streaming market.

In conclusion, the advent of streaming services and the favorable low interest rate environment have created music rights as a natural target for private equity funds as they can provide stable, long-term and above market returns that are based on privately held assets that are perceived as being relatively undervalued. However, as with every hyped-up asset class the question of what the future holds arises.

On the one hand the music rights craze might end in tears for many investors for several reasons. First, it is uncertain if the royalties can actually support the level of cash flows that investors expect considering the high multiple valuations. Second, while streaming is certainly here to stay, the ultra-low interest environment might not. With an annual IRR of allegedly only around 4% a portfolio of expensive music rights could be painfully affected in its valuation should fixed income yields increase in a sustained manner. Lastly, given the nearly non-existing transparency when it comes to NAV calculations there might be a rough awaking from this as well. A fitting example for the transparency issues is again the current leader of the pack Hipgnosis. As a buy-and-hold investor the specialist fund does not expect to sell catalogues. This implies that there will not be any confirmation of the discounted cash flows valuation any time soon. Thus, the market might have a long lead time to catch up to the long-term value of the purchased catalogues based on the long-term royalties they earn. That final valuation could be very different from what the catalogues were purchased for in the first place. Notwithstanding, the current market climate for music rights leads to an immediate uplift in valuations of recently purchased catalogues. Funds such as Hipgnosis are more than happy to book these ‘capital gains’ in order to raise more equity and buy evermore assets in a self-reinforcing cycle. As all of this is based on untransparent but exceedingly high annual revenue multiples the music industry might very well be in bubble territory already.

On the other hand, a sustained bullish perspective nurtured by the investors is that the value and return generation has only just begun for the world’s favorite oldies. Streaming revenues are still set to grow close to 10% per year for the foreseeable future and royalty agreements with growing social media networks such as TikTok might provide for yet not even thought of returns far into the future.

If the gamble on music rights pays-off remains to be seen. Nearly all current investors are explicitly in it for the long-term. Hence, it most certainly will take a while until we know for certain if the sky-high valuations will have provided the expected steady stream of riskless royalty payments and investors will have indeed made “money for nothing” as the Dire Straits famously described the music industry in one of their songs or if there will be awkward silence when the curtain falls.

Author: Joerg Friedl

Editor: Konstantin Brandt

Comments are closed.