by Andrea Villa, Maxine Bruhn-Léon, and Victoria Rakitin

Introduction

This article explores the momentum behind ESG (Environment, Social and Governance) criteria in the global sphere, examining the approach that both international leaders—the European Union and the United States—and market leaders—represented by a discussion of the public and private markets—are adopting ESG. In the former instance, we identified a stronger interest by the European Union to raise ESG criteria regulations, as opposed to its U.S. counterparts. Evidence of this is presented via a comparison of drafted and current legislation concerning ESG principles, such as the EU Taxonomy and the European Green Deal, versus legal actions by the United States Security Exchange Commission and the Department of Labor. In the latter instance, we compared diverging approaches to the adoption of ESG principles between PE-backed companies and publicly listed companies, focusing on stakeholder interests, transparency requirements, and incentives for value creation.

The Impact of ESG Principles

ESG is a term used to describe a collection of non-financial evaluation criteria that assess the robustness of a company’s governance mechanisms and its ability to effectively manage its environmental and social impacts. It directly refers to the environmental, social, and governance principles that command a firm. Examples of ESG data include the quantification of a company’s greenhouse gas emissions, reports on product liabilities regarding safety quality, and information about the compensation of executives. Those metrics are not commonly a mandatory part of financial reporting, but companies are progressively starting to make disclosures in their annual report or in a standalone sustainability report. Indeed, listed companies are under increasing investor pressure to act on everything from executive pay to carbon emissions (“Trends on the sustainability reporting practices of S&P 500 Index companies”, Governance and Accountability Institute, 2020). These growing constraints make the status of private company (who have a higher degree of freedom on governance) more and more attractive and help explain the recent wave of buyouts by private equity firms.

Indeed, 2021 was a record year for PE companies: private equity-backed M&A deals more than doubled, hitting a record high at $818.4bn in the first nine months of this year, up from $315.2bn last year, according to Refinitiv. Based on what has been said so far, it seems that adopting high ESG standards, thereby imposing restrictions, worsens company performance in the short term. However, there is an overwhelming amount of research that points towards a strong, positive correlation between ESG implementation and superior investment returns (Gunnar Friede et al., “ESG and Financial performance: Aggregated evidence from more than 2000 empirical studies, “Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment, October 2015), as will later be explained in this article.

In spite of this, the ESG push among publicly traded companies continues to generate hostile reactions and scepticism in the private companies domain, but many PE firms are not waiting for ROI studies to prove true before betting on implementing ESG practises.

Sensing that broader economic forces are rapidly changing behaviours and attitudes, a growing segment of the industry believes that investments in sustainability, social welfare and good governance require different metrics for now. Indeed, the main reason behind the success of the PE industry in the past may be found in its ability to anticipate future trends of value creation, and there is a meteoric increase in data that suggests that ESG is part of the case (Mozaffar Khan, George Serafeim, and Aaron Yoon, “Corporate sustainability: First evidence on materiality,” The Accounting Review, November 2016).

ESG in Publicly Listed Companies and PE-backed Companies

The adoption of ESG criteria by companies derives both from regulatory requirements and incentives that directly motivate companies to follow ESG criteria to a greater or lesser degree. Publicly listed companies are subject to stricter transparency requirements and national regulations, having to publish comprehensive financial and non-financial information which may include annual sustainability and corporate governance reports. Furthermore, in the wake of numerous scandals originating from governance failures (i.e., Enron), investors have been demanding more transparency and best practices.

Beyond corporate governance aspects, investors have increasingly integrated environmental and social factors as non-financial considerations in their investment decisions. It is therefore in the interest of a company looking to attract equity investment from investors to fulfill such criteria. Being ESG-compliant may also determine if a company is able to operate in the long-term as climate change becomes a more serious issue and can expose the company to physical and transition risks.

While common standards for financial reporting have existed for a long time, reporting on non-financial information has only more recently been subject to initiatives to define and harmonise them to improve transparency and accountability. The European Commission has recently developed several directives such as the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), requiring certain large companies to disclose information on the way they operate and manage social and environmental challenges. The CSRD is applicable to essentially all large private companies or listed companies. The Regulation on Sustainability-related disclosure in the financial services sector (SFDR) is applicable also to PE funds. Directives as such allow investors, civil society organisations, consumers, policy makers and other stakeholders to evaluate the non-financial performance of large companies and encourage these companies to develop a responsible approach to business.

The adoption of ESG criteria may also be a deliberate strategic decision by governing organs of a public company to increase the perceived brand value, enabling it to charge higher prices and increase revenues. Furthermore, adopting ESG criteria facilitates raising capital through sustainability or ESG-linked loans: cheaper loans that include a spread discount depending on if the borrower meets specific sustainability goals or not—potentially saving companies millions of dollars. It is in the interest of a bank to supply ESG-linked loans as they can help lower financing costs, given that companies with strong ESG policies tend to have good track records for profitability and debt repayment.

Incentives for public companies to adopt ESG criteria are also influenced by the interests of its various stakeholders. According to an article by the Journal of Sustainable Finance and Investment by Gunnar Friede et al, 2015, aggregated evidence from more than 2000 empirical studies showed that 63% of the studies showed a positive correlation between ESG propositions on equity returns, meaning it is in the interest of shareholders to push the company to integrate an ESG framework.

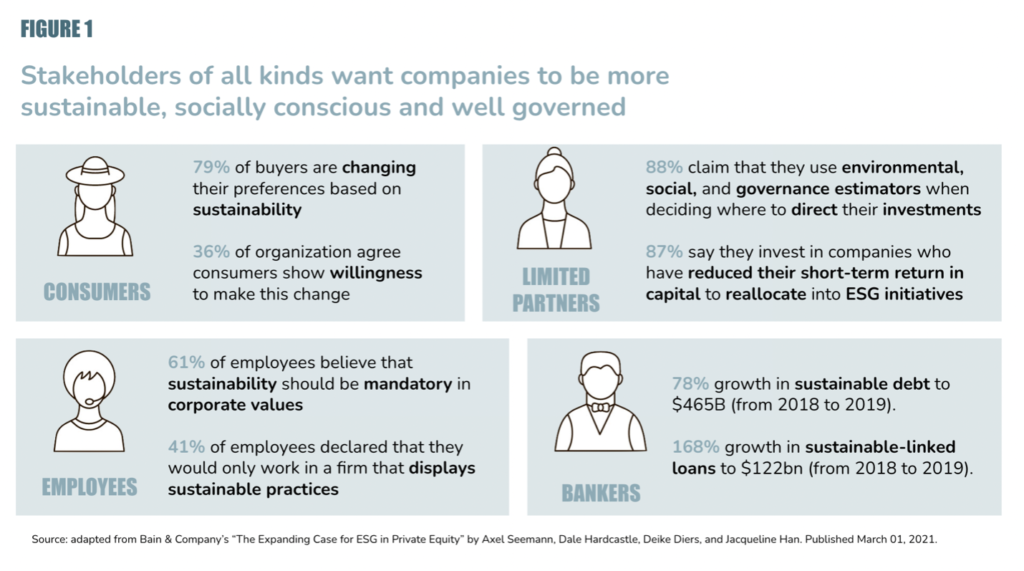

Interestingly, as seen in Figure 1 representing data from a 2020 Capgemini survey of 7,500 consumers and 750 executives globally, 41% of surveyed employees claimed that they would only work for a company with sustainable business practices, while 87% of limited partners asserted that they are looking to invest in companies who have shown commitment to ESG in the long-term by reducing their near-term return in capital in favor of ESG-imitative investments. On a similar thought, customers are also shifting their preferences to more environmentally friendly products and prefer to buy products or services from companies with a lower environmental footprint: 79% of buyers are showing signs of changing their preferences, guided by sustainability principles.

PE-backed companies are not subject to the same, strict, transparency requirements as publicly listed companies. Consequently, stakeholder pressure is less severe. Through a lower level of regulation, PE-backed firms may not need to integrate ESG criteria to the same extent.

The degree of adoption of ESG factors is, however, dependent on the level of influence and control of the PE fund and its strategy: PE funds may either have a sustainability focused strategy as a differentiating factor, promote ESG but not necessarily have a sustainability focus, or may not integrate ESG considerations at all.

However, the tightening EU regulation on ESG reporting will require all funds in the EU to report on sustainability risks as well as any negative impact its investments in PE-backed firms could have on climate, environmental or social factors.

A recent working paper by the European Investment Fund on ESG considerations in Venture Capital (VC) and Business Angel investment decisions,2020, based on two surveys among EU funds, found that ‘’ESG investing appears to be accelerating into the investment mainstream, as approximately 7 in 10 VCs and 6 in 10 Business Angels incorporate ESG criteria in their investment decision process.’’

Furthermore, there is evidence that PE-backed firms are likely to perform better than public firms when it comes to ESG ratings: a report by Lund University on Private Equity Firms and ESG analyses the difference in ESG performance between PE-backed companies that went public through an IPO and companies that went public without being backed by a private equity firm. The report also mentions that “PE firms’ reasoning to work with ESG is found to be very much in line with “regular”companies, which are risk management and value creation, with value creation being the dominant reason.” The results of their experiment, summarised by a statistical t-test, found that PE-backed firms that went public have a 10% higher ESG performance than firms that went public without being backed by PE.

However, it can be argued that for a firm to be backed by PE in the first place, it ideally already follows above-average ESG practices. Investors increasingly look for such criteria since it may lower risk for the future or add value in ways that make the investment more lucrative. Additionally, as a PE firm goes public, for example through an IPO, it may be subject to ESG assessments, as an article published by EY mentions: “A private company that clearly communicates its commitment to ESG, sends a strong signal to the market that it has a capable, forward-thinking leadership team that can drive post-IPO success.”

Diverging ESG Interests Between Europe and the United States

Recently, Europe has adhered to a series of reforms spearheaded by organizations such as the Network for Greening the Financial System—that works on sustainability risk—and the Financial Stability Board—that through its freshly-instituted Task-Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) addresses climate change risk—as a response to growing trends in ESG. Most recently, the Europe-based International Financial Reporting Standards Foundation released the International Sustainability Finances Board (ISSB) to form a baseline for sustainability disclosures that can meet investor needs and answer conscious consumers’ demands for transparent reporting.

Through it all, there appears to be a closer interest in ESG propositions by European PE firms than by their U.S. counterparts. In fact, out of the top 20 institutional investors based in Europe, close to 16 of them have shown a commitment to either the Principles for Responsible Investment, the United Nations’ Net-Zero Asset Owner Alliance, or the TCFD; meanwhile, less than 10 of the top 20 North American institutions have done the same. Interestingly, out of these 10 PE investors, most are based in Canada and not the U.S. (Figure 2).

This finding shows that there is a divergence between European and US institutional investors when it comes to investing in ESG principles. The key explanation lies in the fact that Europe is consistently developing a centralized ESG infrastructure focused on disclosure, transparency, and use of a common language in measuring impact that the U.S., with its laissez-faire approach, still lacks.

For instance, the European Commission announced last year the European Green Deal as a means to establish a sustainable climate strategy that will allow the EU to be climate neutral by 2050. For the PE sector, this means taking public investments to derisk private investments, facilitating PE firms to fund riskier companies that abide by the ESG pillars over less risky ones that do not. The Green Deal helps PE firms to internalize ESG standards by encouraging limited and general partners to directly consider principles of environmental safety, social welfare, and transparent leadership when evaluating where to place their money.

The EU Taxonomy is another key player in modelling Europe’s ESG infrastructure. Six environmental objectives are defined: (i) climate change mitigation; (ii) climate change adaptation; (iii) sustainable use and protection of water and marine resources; (iv) transition to a circular economy; (v) pollution prevention and control; and (vi) protection of healthy ecosystems. Under technical screening criteria that determine how well a firm sustainably contributes to at least one objective and poses no significant harm to the other objectives, the degree of a company’s alignment with the Taxonomy can be measured. This can help private investors determine the suitability of a company for their investments, creating security and transparency in the process.

While Europe has legally committed to ESG standards in the long-term, the U.S. is being left behind. Despite sustainable investment gaining momentum in the last two years with a 40% growth in ESG assets, the U.S. market faces fresh challenges through the ESG investment world, as seen with recent policy changes by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the Department of Labor (DOL).

In 2020, SEC issued amendments to the “shareholder proposal rule” that outlines the process an investor must undergo to have its proposal considered by all shareholders in a firm’s proxy statement. In updating the initial submission criteria, it is now harder for an investor’s resolutions to be taken into account in corporate annual meetings, raising concerns that it will dissolve pressure on U.S. companies to improve their standing on ESG issues. Likewise, in the same year, the DOL adopted a rule that encourages fiduciaries to use financial principles—and consequently completely disregard nonfinancial principles including ESG metrics—to screen pension investments. Both of these suggest that the U.S. is moving in the wrong direction, making it easier for companies to straightforwardly sidestep efforts to adopt and promote ESG assessment.

So what happens when the paths of European and U.S. PE firms differ so greatly? Without coordination, their conflicting regulatory regimes pose a threat to international trade and investment flows. We can already see this taking shape with the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) which sets a tariff on carbon-heavy products imported from non-EU countries with weaker climate laws. While the Biden administration has pushed against the CBAM, all signs point toward the EU adopting this measure as soon as 2023. The U.S. can either react as it has historically done under the Trump administration with retaliatory tariffs or jump on the ESG bandwagon and draw up plans to decarbonize its economy.

Conclusion

Despite the changes that have taken place in recent years, it is impossible not to notice the substantial differences that still exist between public and private companies in the adoption of ESG standards. PE-backed companies do not have to meet the same strict requirements of public ones and therefore, do not have the same incentive structure. Even though incentive structure differs, studies have shown that PE-backed companies adhere to higher ESG standards than their public counterparts do.

Moreover, the present article highlighted the distinction between Europe and the United States with respect to ESG practices of institutional investors. While the European investors are trying to encourage investments in companies that abide to ESG pillars through the Green Deal and to make reporting more homogeneous, the US investors are following a less regulated approach.

In a time where uncertainty and change have become the rule rather than the exception, the rise of ESG and its impact on the public and private markets is bound to make an impact. Divergent approaches to ESG by market and international leaders, however, will determine who leads the curve, and who falls behind it.

Sources

https://www.gartner.com/en/finance/glossary/environmental-social-and-governance-esg

https://www.cfainstitute.org/en/research/esg-investing

https://www.ft.com/content/7e8edfd5-fccd-4f3c-9fda-c616b805c856

https://www.ft.com/content/7e8edfd5-fccd-4f3c-9fda-c616b805c856

https://www.bain.com/insights/esg-investing-global-private-equity-report-2021/#

Editor: Tara Morgan

Comments are closed.