By Erlend Brevik, Fabian Zähringer, and Thor Arne Höfs

Sovereign Wealth Funds (SWFs) are state-owned institutional investors that own, invest, and manage a variety of assets – such as stocks, bonds, real estate, or other alternative investments – to achieve national objectives. Overall, objectives of SWFs can be grouped in several different categories:

1. Capital maximisation

2. Economic development

3. Stabilisation

These objectives may change over the lifetime of the SWFs, while the capital preservation and maximisation dominates over the life of most funds.

The Assets Under Management (AUM) of SWFs has increased substantially

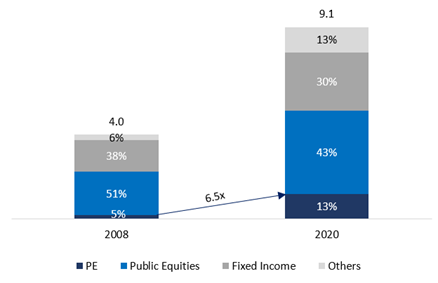

SWFs have become an important force in the global financial markets, as AUM has increased by 2.3x from USD 4.0tn in 2008 to USD 9.1tn in 2020. In the same period, Public Pension Funds (PPFs) have increased AUM from USD 9.9tn to USD 18.4tn. This gives a total AUM of USD 27.5tn in 2020 for SWFs and PPFs combined, according to Global SWF. Figure (1) displays the historical and expected growth of SWFs AUM indicating an expected compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 5.7% from 2020 to 2030. Due to their size, SWFs are able to strongly influence local and global economies. Therefore, it is important to take a closer look at the recent investment trends of SWFs to gain a better understanding of future investment opportunities. SWFs’ asset allocation strategies are impacted by a low interest rate environment, which renders most fixed income assets, such as government bonds, less attractive. With global macroeconomic conditions worsening in times of Covid-19, the pressure on SWFs to finance the national spending gap increases, forcing them to consider different asset classes with higher risk-return profiles.

Figure (1): Growth and estimates for SWFs total AUM (USDtn)

SWFs have delivered solid returns historically

Figure (2): Returns of SWFs vs MSCI World Equity Index 2008-2020

In the period between 2008 and 2020, SWFs have generally had somewhat lower returns and risk than global equities, partly due to exposure to less risky asset classes such as fixed income (30% asset allocation in 2020). The year of 2020 was a relatively weak year for SWFs, with a total return of -2%, while the MSCI world equity index had a total return of 17%.

Increased level of asset allocation to Private Equity

Over the next few years, an increase of alternative investments is expected to achieve the desired return profile of the SWFs. The focus will most likely be on private equity and infrastructure investments, as they match the intention of many SWFs to invest over a longer time period to promote the stabilisation of the economy.

The search for higher yields in a context of very low interest rates has caused the level of asset allocation to private equity to increase substantially during the period of 2008 to 2020, with 13% of SWFs’ AUM being invested in Private Equity in 2020, up from 5% in 2008. Figure (3) represents an increase in SWF Private Equity investments of 6.5x from USD 0.2tn to USD 1.2tn in 2008 to 2020.

Figure (3): Total SWF AUM with split per asset class (USDtn)

Today, 17 of the 20 largest SWFs are invested in Private Equity (see figure (4)), acting not only as limited partners (LPs) but also as co-investors alongside the general partners (GPs). The low prevailing yields on traditional asset classes and the scarcity of high-quality opportunities in other alternatives such as Real Estate and Infrastructure may result in a further drive into Private Equity by SWFs.

Norges Bank Investment Management (NBIM), the world’s largest SWF with over USD 1.2tn AUM has requested multiple times to be allowed to invest in private equity, but the requests have been turned down by the Norwegian government. In 2019, the fund requested to have up to 1% of its equity portfolio in unlisted companies (totalling to USD 7bn at the time), targeting large companies with other institutional investors that are not yet listed. Representatives from the fund have argued that investing in only public companies causes a risk to only invest in outdated business and technology. The recommendation has however met criticism from leading Norwegian academics as they stress the importance of liquidity and transparency. Currently, the fund is limited to invest in unlisted companies which has stated a clear intention of floating. In 2019 the fund was, however, allowed to invest in unlisted renewable energy infrastructure within its environment-related mandates which was increased from NOK 60bn to NOK 120bn in the same year.

Figure (4): Overview of the top 20 SWFs and their asset allocation

In 2020, Abu Dhabi’s SWF Mubadala took a stake in the US private equity group Silver Lake which it planned to follow up with a further USD 2bn backing in a new longer-term investing strategy from the firm. This new strategy with a 25-year time horizon goes beyond the 10-12 years traditionally seen in PE funds, resulting in significantly higher flexibility and a wider range of investment opportunities than those available for traditional PE funds. This signals what kind of impact SWFs can have on private equity, both as an important source of AUM and in enabling new PE fund structures and investment opportunities. With c.USD 230bn, AUM Mubadala was the 11th largest SWF globally in 2020 and is among the most active SWFs in PE investments. In 2020, the fund also committed to invest USD 1.2bn in Mukesh Ambani’s Jio Platforms as it joined Facebook and several US PE groups (incl. Silver Lake) in backing the Indian telecom and digital services business. Mubadala has also previously invested USD 15bn in Softbank’s USD 100bn Vision Fund.

Relative to other institutional investors, SWFs typically have a greater tolerance for the illiquidity inherent in PE investments, allowing many SWFs to build PE allocations that may not be feasible for other investor types, as seen with the Mubadala’s backing of Silver Lake’s new longer-term investment strategy. SWFs have used the current low-yield environment to increase the sophistication in the construction of their investment portfolios in order to ensure high returns for future generations. This has resulted in a significant increase in the SWFs investment in PE, as shown in figure (3).

Some SWFs still exclude private equity from their investment strategy due to liquidity requirements in their mandates and to avoid owning illiquid assets in periods of economic distress. Preqin reported in 2016 that only 20% of SWFs with under USD 1bn AUM invested in private equity, while larger SWFs are more likely to do so, as seen in figure (4).

Preqin also finds that Middle East- and Asia-based SWFs constitute the largest portion of SWFs investing in PE with 62% of SWFs invested in private equity being located these regions. In comparison, only 10% of SWFs invested in private equity are located in Europe (Preqin, 2016).

When it comes to strategy preferences, buyout funds and venture capital funds are the most popular among SWFs. The larger size of buyout funds are attractive to SWFs as they allow to put large amounts of capital to work, while venture capital funds allow for the nurture of domestic enterprises and support the economic development initiatives of the fund. Additionally, co-investing alongside PE fund managers has increased in popularity. This is because it provides portfolio diversification, increased exposure to high-quality PE assets (for which the SWFs themselves have analysed the risk and reward separately), better transparency, and mitigation of the so-called J-curve effect (most PE fund returns are realised when the fund is close to maturity), as capital is deployed faster with single investments.

Even though only 10% of SWFs investing in PE are European, Europe is the most attractive region for SWFs’ PE investment with 79% of PE-investing SWFs being invested in the region, followed by North America at 65% (Preqin, 2016). On the contrary, despite containing some of the largest SWFs, only 51% of PE-investing SWFs target PE investments in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. However, this number has most likely increased in recent years due to MENA-based SWFs pursuing increased direct private equity investments to support domestic social and economic initiatives.

Data from BCG shows that in the first half of 2019, private investments dominated public ones in SWF-backed deals with 105 private deals compared to 16 public deals and a total private deal value of USD 10.1bn for private deals, compared to USD 6.2bn for public deals. Within private investments, PE was the most popular asset class, representing 56% of investment value, while venture capital came in second with 26%. In terms of deal count, VC had 48 compared to 44 for PE. Most of the private investments are done in partnerships, with only 28% of private SWF investments being completed without one, according to the study.

SWFs are still under-allocated to PE

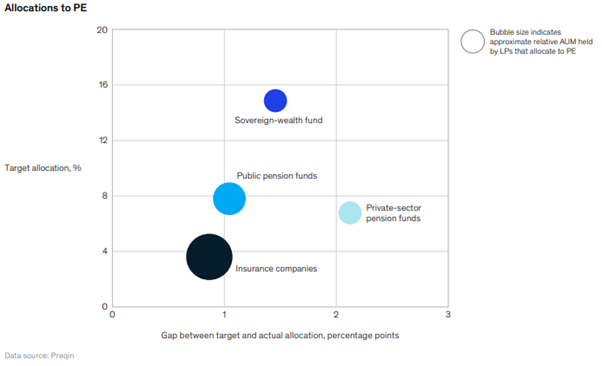

Figure (5): All major LP types are under allocated to PE

Private market AUM grew by 10% in 2019 and 170% (USD 4bn) from 2009 to 2019, compared to 100% for public market AUM in the same period. LPs continue to raise their target allocations to private markets. In private equity alone, LPs appeared to be under-allocated by more than USD 500bn when compared to their target levels. This figure is as large as the global amount raised for private equity in 2019, signalling further growth ahead. As shown in figure (5), among the major LP types with allocation to private equity, SWFs have by far the highest target allocation. In McKinsey’s 2020 Global Market Review, it can be seen that SWFs are still under-allocated versus their target levels by ~1.5 percentage points. With the number of SWFs including PE in their investing mandates and the percentage of capital targeted to PE increasing, this represents a major source of future growth for upcoming private equity fundraising.

SWFs investing in venture capital

Private equity is not the only asset class that has gained the interest of SWFs. Venture capital is also climbing the list as SWFs are shifting towards riskier investment with higher upward potential. Moreover, investments in VC support economic growth and stabilisation. SWFs have participated in approximately USD 17bn of venture capital deals in the first six months of 2020, equalling the investments of the whole year of 2019. With increased dry-powder and a longer investment horizon, SWFs’ interest in start-ups, especially in the technology sector, grows significantly.

One of the largest deals in 2020 has been Abu Dhabi-based Mubadala’s USD 3bn investment in Waymo, an autonomous driving technology company owned by Alphabet. The high valuations of mature companies and the low interest rates on debt investments has shifted interest to healthcare and technology start-ups over the years. Other large deals of 2020 include Singapore’s Temasek Holdings’ USD 3bn investment in Chinese live-stream platform Kuaishou and Cool Japan Fund’s USD 3bn investment in Indonesian ride-hailing and payment company Gojek.

Conclusion

To conclude, SWFs have grown to become very important players in the financial markets with over USD 9tn in total AUM, (or USD 27.5tn including PPFs) and strong presence in most asset classes. In particular, SWFs have increased their allocation to PE and VC, which represent 13% of all SWF investments globally and are included in the mandate of 17 of the 20 largest SWFs. We expect SWFs to further increase their allocation to private equity in the near future, driven by the current gap between target and actual allocation to PE, an increased number of SWFs including PE in their investment mandates, and a continuously increasing percentage target allocation to PE among SWFs.

Authors: Erlend Brevik, Fabian Zähringer, Thor Arne Höfs

Editor: Tiago Guardão

References

https://globalswf.com/reports

https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/sovereign-wealth-investment-funds/publications/assets/sovereign-investors-2020.pdf

https://www.reuters.com/article/us-swf-investment-venture-capital-idUSKBN2402B0

https://www.msci.com/documents/10199/178e6643-6ae6-47b9-82be-e1fc565ededb

https://www.ft.com/content/c95e08b2-c977-11e9-af46-b09e8bfe60c0

https://www.ft.com/content/6695577a-9bc0-4da1-aee5-738a2d08a0eb

https://docs.preqin.com/newsletters/pe/Preqin-PESL-June-16-SWFS-Investing-in-Private-Equity.pdf

https://image-src.bcg.com/Images/BCG-Universita-Bocconi-Sovereign-Wealth-Funds-Newsletter_tcm9-234129.pdf

https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/industries/private%20equity%20and%20principal%20investors/our%20insights/mckinseys%20private%20markets%20annual%20review/mckinsey-global-private-markets-review-2020-v4.ashx

Comments are closed.